Research Findings #3: Access to Health Care - Sources and Barriers,

1996

Robin M. Weinick, Ph.D., Samuel H. Zuvekas,

Ph.D., and Susan Drilea, M.S.

Introduction

Adequate access to health

care services can significantly influence health

care use and health outcomes. Consequently, measures

of access to care provide an important mechanism

for evaluating the quality of the Nation's health

care system. Limitations in access to care extend

beyond such simple issues as a shortage of health

care providers or facilities in some areas. Even

where health care services are readily available,

individuals may not have a usual source of health

care or may experience barriers to receiving services

because of financial or insurance restrictions,

a lack of availability of providers at night or

on weekends, or other difficulties.

This report describes several

aspects of access to health care in America in 1996,

including the proportion of the population lacking

a usual source of care as well as the types and

characteristics of providers used by those who do

have a usual source of care. A number of measures

of satisfaction with the usual source of health

care are presented. Estimates also are reported

on the percentage of American families that experience

difficulty or delay in obtaining health care or

do not receive needed health care services. Specific

comparisons are made by age, race/ethnicity, sex,

perceived health status, health insurance coverage,

and place of residence.

This report presents estimates

of access to health care by the civilian noninstitutionalized

population of the United States during 1996. The

estimates are derived from 1996 Medical Expenditure

Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component (HC) data.

A technical appendix at the end of this report presents

detailed descriptions of the MEPS HC, including

data collection methods, questionnaire items, data

editing, sample sizes, and statistical procedures

for deriving estimates.

^top

Usual

Sources of Health Care

Access to health care is a complex, multidimensional

concept. Having a usual source of health care is one indicator

of access that has been studied extensively. Among other findings,

persons with a usual source of health care have been shown to

be more likely than those without a usual source of care to

receive a variety of preventive health care services (Caplan

and Haynes, 1996; Ettner, 1996; Mark and Paramore, 1996; Martin,

Calle, Wingo, et al., 1996) and to receive treatment if they

have hypertension (Moy, Bartman, and Weir, 1995).

Table 1 presents

a profile of Americans' usual sources of health care in 1996.

Nearly 18 percent of the population (17.6 percent) did not have

a usual source of health care. Thus, more than 46 million Americans

had no particular doctor's office, clinic, health center, or

other place that they would usually go if they were sick or

needed advice about their health. Among those who did have a

usual source of health care, 88.3 percent (72.7 percent of all

Americans) had an office-based provider and 11.2 percent (9.2

percent of all Americans) had a hospital outpatient department

or clinic as their usual source of care.

Population Characteristics

Americans' usual sources of health care

can vary among groups with different demographic and health-related

characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, sex, perceived

health status, health insurance coverage, and place of residence.

Age

Young children and elderly adults were

more likely than adults ages 18-64 to have a usual source of

health care. Still, 5.5 percent of children under age 6, representing

more than 1.3 million children, did not have a usual source

of health care. Likewise, 9.2 percent of persons age 65 and

over had no usual source of health care.

Approximately 23 percent of persons ages

18-64 had no usual source of health care (not shown in Table

1). Young adults ages 18-24 were more likely than any other

age group to lack a usual source of health care (34.0 percent).

Race/Ethnicity

Among the racial/ethnic groups considered

in this report, Hispanics were the least likely to have a usual

source of care. Almost 30 percent (29.6 percent) of Hispanics

lacked a usual source of care, compared with 20.2 percent of

blacks and 15.5 percent of a combined category of whites and

other racial/ethnic groups.

Among those who had a usual source of

care, blacks and Hispanics were more likely than those in the

group of whites and others to have hospital-based providers

(including hospital clinics and outpatient departments) as their

usual source of care. Conversely, whites and other racial/ethnic

groups were more likely to have an office-based usual source

of care.

Sex

Males were substantially more likely to

lack a usual source of health care than females (21.3 percent

versus 14.1 percent). Males were also less likely than females

to have an office-based usual source of care (69.3 percent vs.

76.0 percent).

Perceived

Health Status

Persons whose perceived health status

was poor were more likely to have a usual source of health care

than persons whose health status was reported to be excellent,

very good, or good. Even so, 10.1 percent of those whose health

status was reported to be poor had no usual source of health

care; this represents nearly 800,000 Americans.

Health Insurance Coverage

Health insurance coverage can be an important

determinant of many aspects of access to health care. Table

1 shows that persons under age 65 who were uninsured were

substantially more likely to lack a usual source of health care

(38.0 percent) than those who had either private (14.5 percent)

or public health insurance (13.3 percent). When compared with

their counterparts who had private health insurance, persons

under age 65 who were uninsured were 2.6 times more likely to

lack a usual source of health care. Persons under age 65 who

had private insurance were more likely to have an office-based

usual source of care (77.2 percent) than those who had public

insurance (70.8 percent) or were uninsured (51.8 percent).

Individuals age 65 and over who had Medicare

as their only health insurance coverage were more likely to

lack a usual source of health care (11.9 percent) than persons

with Medicare and additional public or private insurance coverage

(7.7 percent; not shown in Table 1). In addition, among persons

age 65 and over who had a usual source of health care, those

with health insurance coverage in addition to Medicare were

more likely to have an office-based usual source of care than

those for whom Medicare was the sole source of insurance (not

shown in Table 1).

Metropolitan Statistical Areas

Americans living in metropolitan statistical

areas (MSAs) were more likely to lack a usual source of health

care (18.1 percent) than those living outside of MSAs (15.8

percent).

Other Characteristics

Other important aspects of access to care

include reasons why people change their usual source of care,

types and characteristics of usual sources of health care, and

satisfaction.

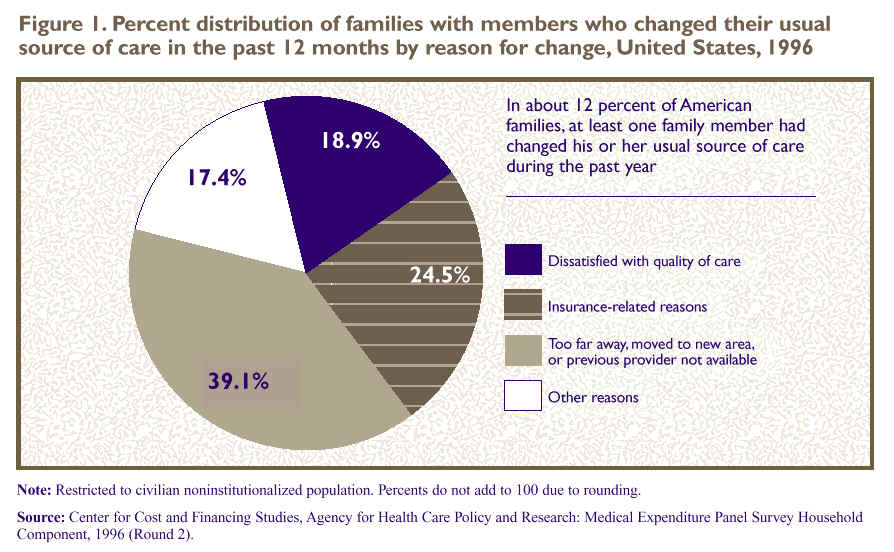

Changes in Usual Source of Care

The extent to which individuals change

their usual source of health care is of interest when examining

access to health care, as it may reflect a lack of continuity

of care, dissatisfaction with care, or poor quality. In approximately

12 percent of American families, at least one member had changed

his or her usual source of health care within the 12-month period

prior to the survey date. To the extent that this represents

an annual rate of change in usual source of care, it suggests

a fairly high rate of turnover in the long run. The reasons

why family members changed their usual source of health care

are displayed in Figure 1. Nearly 25 percent

(24.5 percent) of the families with members who changed their

usual source of care switched for insurance-related reasons,

including having changed health insurance plans or the insurance

plan having changed the doctors it covers. Another 18.9 percent

had family members who made a change because they were dissatisfied

with the quality of care they ere receiving. Almost 40 percent

(39.1 percent) had changed their usual source of health care

because their provider was too far away, they had moved to a

new area, or their previous provider was no longer available.

The remaining 17.4 percent changed their usual source of care

for a variety of other reasons, such as a change in their health

care needs.

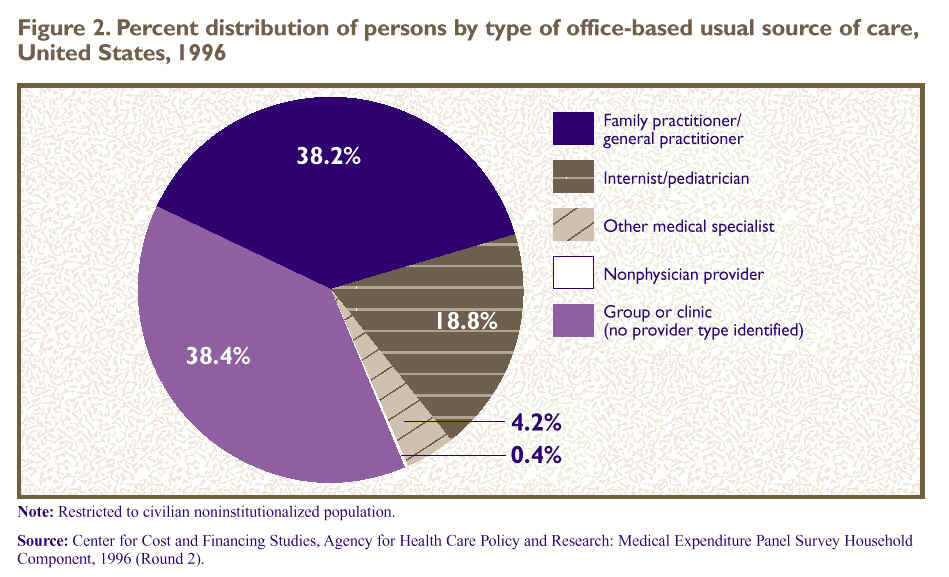

Types of

Office-Based Providers

Figure 2 displays

the types of health care providers for the 72.7 percent of Americans

who had an office-based usual source of health care. Of this

group, 38.2 percent had a family practitioner or general practitioner,

18.8 percent had an internist or pediatrician, and 4.2 percent

had another medical specialist--such as an obstetrician/gynecologist

or surgeon--as their usual provider. Another 38.4 percent had

a group or clinic practice as their usual source of health care,

without a particular provider type identified.

Nonphysician providers, including nurses,

nurse practitioners, physician's assistants, midwives, and chiropractors,

comprised less than 1 percent of office-based usual sources

of care for Americans in 1996. However, because many nonphysician

providers practice in group or clinic settings, this probably

understates the impact such providers have on the health care

of the American population.

Characteristics of Usual Sources

of Care

Table 2 describes

the characteristics of Americans' usual sources of health care

(excluding emergency rooms). Nearly half (48.6 percent) of people

whose usual source of health care was either office based or

a hospital outpatient department or clinic had providers with

office hours at night or on weekends. They represented nearly

105 million Americans. Approximately three-fourths (76.3 percent)

usually had an appointment to see their provider, and 23.2 percent

(or 50 million people) found it very difficult or somewhat difficult

to contact their provider by telephone.

Continuity of Care and Satisfaction

Continuity of care and satisfaction with

usual source of health care are additional aspects of access

to care, and they are also key components of quality health

care. Table 3 profiles several dimensions

of satisfaction and continuity of care for the 82 percent of

Americans who had office-based, hospital outpatient department,

or hospital clinic providers as their usual source of care.

Levels of satisfaction with the usual

source of health care were quite high. Nearly all Americans

whose usual source was not an emergency room were "somewhat

satisfied" or "very satisfied" with the overall

quality of care received (97.1 percent) and with the professional

staff (95.5 percent). An equally high proportion of people (96.6

percent) had a usual provider who generally listened to them

and gave them the information they needed about health and health

care. Likewise, 95.9 percent were confident in their usual provider's

ability to help when they had a medical problem. Americans who

had a usual source of health care were overwhelmingly satisfied

with and confident in their provider. However, continuity of

care, as measured by whether their usual provider typically

asked about prescription medications and treatments provided

by other doctors, was experienced by only 77.4 percent of Americans

with a usual source of health care.

^top

Barriers

to Care

American families' experiences of difficulty

in obtaining health care, delays in obtaining care, or not receiving

the health care that family members thought they needed are

shown in Table 4. Approximately 12.8 million

families (11.6 percent of American families) experienced difficulty

or delay in obtaining care or did not receive needed health

care services for one or more of the reasons asked about in

the MEPS HC. (These reasons are shown in detail in the technical

appendix.)

Among families that experienced barriers

to care, inability to afford health care was cited by the majority

(59.9 percent) as the main reason for family members' difficulty,

delay, or not receiving needed health care. Another 19.5 percent

cited insurance-related reasons as the main obstacle to receiving

needed health care. These reasons included their insurance company

not approving, covering, or paying for care; having pre-existing

conditions (for which insurance coverage is often restricted);

referrals being required but unobtainable; and doctors' refusing

to accept the family's insurance plan. The remaining 20.7 percent

of families experienced a variety of other problems receiving

health care, including transportation problems, physical barriers,

communication problems, child care limitations, lack of time

or information, or refusal of services.

Barriers to care vary among families with

different demographic and health characteristics, including

race/ethnicity, perceived health status, and health insurance

status.

Race/Ethnicity of Head of Family

Families with a Hispanic head of the family

were more likely to report barriers to receiving health care

(15.1 percent) than those with heads of family who were either

black (9.9 percent) or white or other race/ethnicity (11.4 percent).

Among families that encountered problems in receiving care,

those headed by Hispanics also were more likely (69.1 percent)

than those headed by persons in the white and other group (58.5

percent) to be unable to afford health care.

Perceived Health Status

Families in which any member's health

status was reported as either fair or poor were almost twice

as likely to experience difficulty, delay, or lack of health

care (17.9 percent) as families in which all members' health

status was reported as excellent, very good, or good (9.9 percent).

There were no significant differences by health status in the

types of problems experienced.

Health Insurance Coverage

Families in which one or more members

lacked health insurance were 2.9 times more likely to experience

difficulty or delay in obtaining health care or to not receive

needed care than families in which all members were insured

(not shown in Table 4). For example, families in which all members

were uninsured were more likely to experience barriers to needed

health care (27.1 percent) than the average for all families

(11.6 percent). This represents almost 3.3 million uninsured

families in which at least one family member experienced difficulty

or delay or did not receive needed health care. Among these,

87.0 percent, or nearly 2.9 million families, identified their

main problem as being unable to afford care.

Families in which only some members were

uninsured were more likely to experience barriers to needed

health care than the average family. Table4 shows

that problems were experienced by:

-

18.1 percent of families

with some uninsured and some privately insured.

-

21.8 percent of families

with some uninsured and some publicly insured.

-

27.5 percent of families

with some uninsured, some privately insured, and some publicly

insured.

Similarly, among families that experienced

obstacles to receiving health care, those in which one or more

members were uninsured generally were more likely than other

families to report the inability to afford care as their main

barrier. Families in which all members were privately insured

were the least likely to report barriers to care (7.0 percent).

^top

Conclusions

Data from the 1996 MEPS HC indicate that satisfaction

with usual source of health care is nearly universal. Even so, almost

12 percent of families had members who had changed their usual source

of care within the last 12 months, frequently for quality-of-care or

insurance-related reasons. A 12-percent annual rate of change suggests

a potentially high rate of turnover in usual sources of health care

in the long run.

Nearly 18 percent of the civilian noninstitutionalized

population had no usual source of health care in 1996, and almost 12

percent of families had members who experienced difficulty or delay

in obtaining health care or did not receive needed care. However, these

experiences were not distributed evenly across the population. Two

groups were consistently at higher risk of lacking a usual source of

care and experiencing barriers to obtaining care: Hispanics and the

uninsured.

Hispanic Americans were substantially more likely

than other Americans to lack a usual source of health care and were

more likely to use hospital-based sources when they did have a usual

source of care. In addition, families with a Hispanic head of family

were more likely than others to experience obstacles to receiving care,

particularly the inability to afford health care. This lack of access

to health care among the Hispanic population of the United States may

reflect the fact that they were among the most likely to be uninsured

(Beauregard, Drilea, and Vistnes, 1997; istnes and Monheit, 1997).

Lacking health insurance is a major factor associated

with the access-to-care measures presented in this report. Uninsured

individuals under age 65 were substantially more likely than others

to lack a usual source of health care. Similarly, families in which

one or more members lacked health insurance were more likely than other

families to experience obstacles that resulted in difficulty or delays

in receiving care or not receiving needed medical care. Among families

that experienced such barriers, those with uninsured members generally

were more likely than those in which everyone had health insurance

to be unable to afford needed health care.

While there are substantial barriers to access

to health care among persons and families that are uninsured, having

health insurance does not guarantee that health care will be accessible

or affordable. A substantial minority of persons with private health

insurance still reported having no usual source of care. Similarly,

more than two-thirds of privately insured families experiencing barriers

to health care cited affordability or health insurance problems as

the main reason for their difficulty. MEPS results indicate that insurance

coverage is strongly associated with access to health care. Monitoring

the relationship between health insurance coverage and measures of

access to health care will provide important information in future

years as the Nation continues efforts to constrain health care costs

while placing increased emphasis on quality of care.

^top

Tables

Table 1. Percent distribution

of population by usual source of health care and selected population

characteristics, United States, 1996

| Population

characteristics |

Total

population in thousands |

No

usual source of health care |

Usual

source of health care is: |

| Office-baseda |

Hospital

outpatient department or clinicb |

Emergency

room |

| Totalc |

262,654

|

Percent

distribution of population

|

17.6

|

72.7

|

9.2

|

0.5

|

| Age

in years |

| Under

6 |

24,164

|

5.5

|

83.8

|

10.1

|

*0.5

|

| 6-17 |

47,253

|

10.4

|

80.2

|

9.0

|

*0.4

|

| 18-24 |

24,854

|

34.0

|

57.4

|

7.6

|

*1.0

|

| 25-54 |

114,359

|

22.7

|

68.1

|

8.8

|

0.4

|

| 55-64 |

20,899

|

13.2

|

75.2

|

10.9

|

*0.7

|

| 65

and over |

31,125

|

9.2

|

80.3

|

10.1

|

*0.4

|

| Race/ethnicity |

| Hispanic |

28,350

|

29.6

|

57.9

|

11.9

|

0.6

|

| Black |

32,838

|

20.2

|

63.6

|

14.9

|

*1.3

|

| White

and other |

201,466

|

15.5

|

76.3

|

7.8

|

0.3

|

| Sex |

| Male |

127,922

|

21.3

|

69.3

|

8.9

|

0.4

|

| Female |

134,732

|

14.1

|

76.0

|

9.4

|

0.5

|

| Perceived

health status |

| Excellent |

95,817

|

18.4

|

73.0

|

8.2

|

0.3

|

| Very

good |

79,193

|

18.3

|

72.4

|

8.8

|

0.5

|

| Good |

58,405

|

18.0

|

71.9

|

9.5

|

*0.5

|

| Fair |

21,115

|

13.3

|

73.1

|

12.8

|

*0.8

|

| Poor |

7,868

|

10.1

|

77.8

|

10.9

|

*1.2

|

| Health

insurance statusd |

| Under

age 65: |

| Any

private |

161,356

|

14.5

|

77.2

|

8.1

|

0.2

|

| Public

only |

26,278

|

13.3

|

70.8

|

14.5

|

1.4

|

| Uninsured |

43,896

|

38.0

|

51.8

|

9.1

|

1.1

|

| Age

65 and over: |

| Medicare

only |

8,123

|

11.9

|

74.9

|

12.8

|

*0.4

|

| Medicare

and private |

19,344

|

7.5

|

83.4

|

8.7

|

*0.3

|

| Medicare

and other public |

3,056

|

8.9

|

78.3

|

12.2

|

*0.5

|

| Metropolitan

statistical area (MSA) |

| MSA |

208,887

|

18.1

|

72.3

|

9.1

|

0.4

|

| Non-MSA |

53,767

|

15.8

|

74.3

|

9.3

|

*0.6

|

- aIncludes

all types of physicians and nonphysician providers seen in an office

setting as well as office-based group practices or clinics.

- bIncludes

outpatient departments and clinics owned and operated by hospitals.

- cIncludes

individuals with unknown health status and those few individuals

age 65 and over who did not have Medicare. Excludes a small number

of persons who were eligible for data collection in the first half

of 1996 but died or were institutionalized in the second half of

the year. See Technical Appendix for details.

- dThis

refers to health insurance status during the first half of 1996.

Uninsured refers to persons uninsured during the entire period.

Public and private insurance categories refer to individuals with

public or private insurance at any time during the period; individuals

with both public and private insurance are considered privately

insured. CHAMPUS and CHAMPVA (Armed-Forces-related coverage) are

considered private health insurance in this report.

- *Relative standard error

is greater than or equal to 30 percent.

Note: Restricted to

civilian noninstitutionalized population. Percents may not add to

100 due to rounding.

Source: Center for

Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component,

1996 (Rounds 1 and 2).

^top

Table 2. Percent of population by selected characteristics

of usual source of health care, United States, 1996

| Characteristics

of usual source of care |

Percent |

Population

in thousands |

| Has

office hours at night or on weekends |

48.6

|

104,676

|

| Usually

have an appointment |

76.3

|

164,137

|

| Somewhat

difficult or very difficult to contact by telephone |

23.2

|

49,904

|

Note: Excludes

individuals whose usual source of care is an emergency room. Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component,

1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table 3. Percent of population by satisfaction

with usual source of health care and continuity of care, United

States, 1996

| Satisfaction

or continuity of care |

Percent |

Population

in thousands

|

| Somewhat

satisfied or very satisfied with overall quality of care |

97.1

|

208,976

|

| Somewhat

satisfied or very satisfied with professional staff |

95.5

|

205,469

|

| Provider

generally listens to them and gives them needed health information |

96.6

|

207,786

|

| Confident

in provider's ability to help with a medical problem |

95.9

|

206,443

|

| Provider

usually asks about prescription medications and treatments

from other doctors |

77.4

|

166,539

|

Note: Excludes

individuals whose usual source of care is an emergency room. Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component,

1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table 4. Percent of families with members experiencing

difficulty or delay in obtaining health care or not receiving needed

health care by main problem in receiving care and family characteristics,

United States, 1996

Family

characteristics

|

Total

number of families in thousands

|

Percent

with any problem

|

Main

problem

|

Inability

to afford care

|

Insurance-related

reasonsa

|

Other

problemsb

|

| Total |

110,207

|

11.6

|

Percent

distribution of families with problem

|

59.9

|

19.5

|

20.7

|

| Race/ethnicity

of head of family |

| Hispanic |

9,408

|

15.1

|

69.1

|

15.8

|

15.0

|

| Black |

12,770

|

9.9

|

60.4

|

12.3

|

27.3

|

| White

and other |

88,029

|

11.4

|

58.5

|

20.9

|

20.6

|

| Perceived

health statusc |

| Any family

member in fair or poor health |

23,227

|

17.9

|

60.9

|

17.9

|

21.3

|

| All family

members in excellent,very good, or good health |

86,938

|

9.9

|

59.3

|

20.3

|

20.4

|

| Health

insurance status of familyd |

| All members

private insurance |

68,539

|

7.0

|

36.7

|

32.2

|

31.1

|

| All members

public insurance |

12,495

|

12.2

|

46.2

|

21.8

|

32.0

|

| All members

uninsured |

12,125

|

27.1

|

87.0

|

6.0

|

7.0

|

| Some

private, some uninsured |

8,006

|

18.1

|

77.4

|

14.2

|

*8.5

|

| Some

public, some uninsured |

4,250

|

21.8

|

80.8

|

*2.5

|

16.7

|

| Some

private, some public |

3,830

|

12.6

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

| Some

private, some public, some uninsured |

962

|

27.5

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

| Metropolitan

statistical area (MSA) |

| MSA |

87,972

|

11.5

|

59.4

|

19.9

|

20.7

|

| Non-MSA |

22,235

|

12.0

|

61.6

|

17.9

|

20.6

|

- aIncludes

insurance company wouldn't approve, cover, or pay for care; pre-existing

condition; insurance required a referral but couldn't get one;

doctor refused to accept family's insurance plan.

- bIncludes

transportation problems (medical care was too far away, can't drive

or don't have car/no public transportation available, too expensive

to get there); physical problems (hard to get into building, hard

to get around inside building, no appropriate equipment in office);

communication problems (hearing impairment or loss, different language);

and other problems (couldn't get time off work, didn't know where

to go to get care, was refused services, couldn't get child care,

didn't have time or took too long).

- cA

small number of families with missing health status for all family

members are excluded from this breakdown but included in the total

line of the table. See Technical Appendix for details.

- dRefers

to health insurance status during the first half of 1996. Uninsured

refers to persons uninsured during the entire period. The public

and private insurance categories refer to individuals with public

or private insurance at any time during the period; individuals

with both public and private insurance are considered privately

insured. CHAMPUS and CHAMPVA (Armed-Forces-related coverage) are

considered private health insurance in this report.

- *Relative

standard error is greater than or equal to 30 percent.

- Sample sizes

are too small to support reliable estimation.

Note: Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population. Percents may not add

to 100 due to rounding .Source: Center for

Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component,

1996 (Rounds 1 and 2).

^top

References

Beauregard KM, Drilea SK,

Vistnes JP. The uninsured in America--1996. Rockville (MD): Agency

for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. MEPS Highlights No.

1. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0025.

Caplan LS, Haynes SG. Breast

cancer screening in older women. Public Health Review 1996;24(2):193-204. Cohen

J. Design and methods of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;

1997. MEPS Methodology Report No. 1. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0026.

Cohen JW, Monheit AC, Beauregard

KM, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health

information resource. Inquiry 1996;33:373-9.

Cohen S. Sample design of

the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component. Rockville

(MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. MEPS

Methodology Report No. 2. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0027.

Ettner

SL. The timing of preventive services for women and children:

the effect of having a usual source of care. American Journal of Public

Health 1996;86(12):1748-54.

Mark TL, Paramore LC. Pneumococcal

pneumonia and influenza vaccination: access to and use by U.S. Hispanic

Medicare beneficiaries. American Journal of Public Health 1996;86(11):1545-50.

Martin LM, Calle EE, Wingo

PA, Heath CW Jr. Comparison of mammography and Pap test use from

the 1987 and 1992 National Health Interview Surveys: are we closing

the gap? American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1996;12(2):82-90. Moy

E, Bartman BA, Weir MR. Access to hypertensive care: effects of income,

insurance, and source of care. Archives of Internal Medicine 1995;155(14):1497-1502.

Vistnes JP, Monheit AC. Health

insurance status of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population:

1996. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;

1997. MEPS Research Findings No. 1. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0030.

^top

Technical

Appendix

The data in this report were

obtained in the first and second rounds of interviews for the Household

Component (HC) of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS).

MEPS is cosponsored by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality

(AHRQ) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The

MEPS HC is a nationally representative survey of the U.S. civilian

noninstitutionalized population that collects medical expenditure

data at both the person and household levels. The focus of the MEPS

HC is to collect detailed data on demographic characteristics, health

conditions, health status, use of medical care services, charges

and payments, access to care, satisfaction with care, health insurance

coverage, income, and employment. In other components of MEPS, data

are collected on residents of licensed or certified nursing homes

and the supply side of the health insurance market.

The sample for the MEPS HC

was selected from respondents to the 1995 National Health Interview

Survey (NHIS), which was conducted by NCHS. NHIS provides a nationally

representative sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population

and reflects an oversampling of Hispanics and lacks. The MEPS HC

collects data through an overlapping panel design. In this design,

data are collected through a precontact interview that is followed

by a series of five rounds of interviews over 2 1/2 years. Interviews

are conducted with one member of each family, who reports on the

health care experiences of the entire family. Two calendar years

of medical expenditure and utilization data are collected from each

household and captured using computer-assisted personal interviewing

(CAPI). This series of data collection rounds is launched again each

subsequent year on a new sample of households to provide overlapping

panels of survey data that will provide continuous and current estimates

of health care expenditures. The reference period for Round 1 of

the MEPS HC was from January 1, 1996, to the date of the first interview,

which occurred during the period from March through July 1996. The

reference period for Round 2 of the MEPS HC was from the date of

the first interview (March-July 1996) to the date of the second interview,

which took place during the period from August through November 1996.

Information

on Access to Care

A supplementary module on

access to care was administered in Round 2 of the MEPS HC. This supplement

serves a number of purposes in MEPS. It gathers information on three

main topic areas: whether each family member has a usual source of

health care, the characteristics of usual sources of health care

for the family, and barriers the family has faced in obtaining needed

health care.

Usual Source of Health

Care

For each family member, the

MEPS interviewer ascertains whether there is a particular doctor's

office, clinic, health center, or other place that the individual

usually goes when sick or in need of health advice. For those family

members who do not have a usual source of health care, the interviewer

ascertains the reason or reasons why. If any family members changed

their usual source of health care during the 12 months prior to the

Round 2 interview, information is obtained on the reason why this

change was made.

Characteristics of Usual

Source of Health Care

For each unique usual source

of health care provider for a given family, the interviewer asks

for the following information:

-

Is the provider

a medical doctor or some other type of medical provider? (This

question is followed by questions asking either the provider's

medical specialty or the type of nonphysician provider.) Is the

provider hospital based?

-

Is the provider

the person or place that family members would go to for new health

problems, preventive health care, and referrals to other health

professionals?

-

Does the

provider have office hours on nights and weekends? What are the

characteristics of the provider related to appointments and waiting

time? How difficult is it to contact a medical person at the

provider's office by telephone?

Does the provider generally

listen to family members and ask about prescription medications other

doctors may have given them? (This question is followed by a number

of other questions about quality-related characteristics of the provider,

including family members' confidence in and satisfaction with the

care received from the provider.)

Since these questions are

asked once for each usual source of health care provider, responses

represent the average experience of all family embers who use that

provider for their usual source of health care, as reported by the

survey respondent.

Barriers

to Health Care

The interviewer also gathers

information on barriers to health care for the family. The interviewer

asks if any family members have recently gone without needed health

care because the family needed money to buy food or clothing or to

pay for housing. In addition, the respondent is asked to rate his

or her satisfaction with the ability of family members to obtain

health care if needed. Questions are asked to directly assess whether

any family members experienced difficulty obtaining any type of health

care, experienced delays in obtaining care, or did not receive health

care they thought they needed because of:

-

Financial/insurance

problems, including "couldn't afford care," "insurance

company wouldn't approve, cover, or pay for care," "pre-existing

condition," "insurance required a referral, but couldn't

get one," and "doctor refused to accept family's insurance

plan."

-

Transportation

problems, including "medical care was too far away," "can't

drive or don't have car/no public transportation available," and

too expensive to get there."

-

Communication

problems, including "hearing impairment or loss" and "different

language."

-

Physical

problems, including "hard to get into building," "hard

to get around inside building," and "no appropriate

equipment in office."

-

Other problems,

including "couldn't get time off work," "didn't

know where to go to get care," "was refused services," "couldn't

get child care," "didn't have time or took too long," and

other reasons.

Data

Editing and Handling of Missing Data

Minimal data editing was done

on the variables in the access-to-care supplement. Editing consisted

of the construction of new variables from a series of data elements

and some logical editing that was carried out to ensure consistency

among the variables. "Other specify" text fields were reviewed

and either classified into existing categories or put into new categories

created to accommodate this information. issing

data is a relatively small problem for the access-to-care information.

Of the 22,149 individuals who had positive Round 2 person-level weights,

72 were excluded entirely from this report because they were either

dead or institutionalized at the time of the Round 2 interview, making

them ineligible for the access-to-care supplement questions. (The

weighted population estimate for these 72 omitted individuals is

861,629.) This leaves an unweighted population of 22,077 on which

the estimates in Table 1 are based. Of these,

98 were missing data on whether they had a usual source of care,

resulting in an unweighted population of 21,979 for the column "percent

of population with no usual source of health care." An additional

32 people had a usual source of health care but had missing data

on the type of place, resulting in an unweighted population of 21,947

for the last three columns of this table. The strategy of omitting

cases that are missing data is based on the assumption that the unknown

cases are distributed in the same way as the known cases. This strategy

for dealing with missing data is used throughout this report except

where otherwise noted. An additional 15 people for whom health status

was unknown are included in the total line of Table

1 but are not included in the breakdown by health status. Similarly,

48 people who were age 65 and over but not covered by Medicare are

included in the total line but not in the breakdown by insurance

status.

Figure 1 shows

the reasons why family members who changed their usual source of

care in the last 12 months did so. It includes those who lacked a

usual source of care at the time of the interview, but who had one

in the 12 months prior to the interview date. Only 37 families (0.4

percent of all responding families) were missing data on whether

there had been a change in usual source of health care, and an additional

4 families (0.04 percent) had experienced such a change but were

missing data on the reason for the change. They are omitted from

the figure.

Tables 2 and 3 are

based on the Table 1 population (n = 21,947)

but exclude 4,213 people who had no usual source of health care (the

17.6 percent shown in Table 1) and 104 people

whose usual source of health care was an emergency room (the 0.5

percent shown in Table 1). The unweighted population

for Tables 2 and 3 totals

17,630. In addition, Tables 2 and 3 are

affected by small amounts of item nonresponse, as follows:

-

Table

2: Provider has office hours at nights or on weekends (7.2

percent), usually have an appointment (0.3 percent), and difficulty

contacting by telephone (7.7 percent).

-

Table

3: Satisfaction with quality (1.1 percent), satisfaction

with professional staff (1.2 percent), provider generally listens

to them (2.1 percent), confident in provider's ability to help

(1.6 percent), and provider usually asks about prescription

medications (4.8 percent).

For Figure

2, the unweighted population is 15,509--the population for Tables

2 and 3 less 2,121 people whose usual

source of care was hospital based but not an emergency room. The

small number of cases (9) with office-based usual sources of health

care who could not be classified are omitted from Figure

2. Persons included in the "group or clinic" category

are those whose usual source of health care was office based with

no particular individual provider specified.

Table 4 is

a family-level analysis. Of the 9,084 families with positive weights,

1,089 reported any barriers to care. The distribution of reasons

for experiencing difficulty, delay, or not receiving needed health

care is based on 1,088 of these cases; the remaining case did not

specify a type of barrier and is omitted from this distribution.

The reasons for experiencing difficulty, delay, or not receiving

needed care shown in Table 4 are the main reasons

reported by respondents for their families. For families in which

one or more full-time students ages 17-23 were living away at school,

the students' experiences are characterized by those of their families

(i.e., the primary household respondent's response to the question

on barriers to care is assumed to represent the student's experience).

The family characteristics

shown in Table 4 are obtained in two ways.

For race/ethnicity of head of family and place of residence, the

characteristic of the reference person (the person in whose name

the family's home is owned or rented) is used to describe the family.

For 54 cases in which the reference person was missing such data,

available information from the next oldest individual in the family

is used. For perceived health status and health insurance status

of the family, all members who were eligible for data collection

are included in the description of the family. When an individual

was missing data on health status or health insurance, the family

is characterized based on data from the remaining individuals with

nonmissing values. This strategy is based on the assumption that

the health insurance and health status of family members missing

such data are distributed in the same way as for those family members

whose status is known. For the family-level estimates, 792 individuals

were missing health insurance data; 790 of these were not present

in Round 1 of MEPS, the round from which the health insurance information

in this report is derived. (See below.) Similarly, 1,580 people were

missing health status data; 790 of these were not present for the

Round 1 MEPS interview. Three families' health status could not be

determined, as data were missing for all family members. Health insurance

information was available from one or more family members for all

families in Round 2 of MEPS.

Population

Characteristics

All population characteristics

used in this report come from the MEPS HC Round 1 data collection

effort, the most recently available data as of the writing of this

report.

Age

The respondent was asked to

report the age of each family member as of the date of the Round

1 interview.

Race/Ethnicity

Classification by race and

ethnicity is based on information reported for each family member.

Respondents were asked if their race was best described as American

Indian, Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, black, white, or

other. They were also asked if their main national origin or ancestry

was Puerto Rican; Cuban; Mexican, Mexicano, Mexican American, or

Chicano; other Latin American; or other Spanish. All persons who

claimed main national origin or ancestry in one of these Hispanic

groups, regardless of racial background, are classified as Hispanic.

Since the Hispanic grouping can include black Hispanic, white Hispanic,

and other Hispanic, the race categories of black and white/other

do not include Hispanic persons.

Perceived Health Status

The respondent was asked to

rate the health of each person in the family at the time of the Round

1 interview according to the following categories: excellent, very

good, good, fair, and poor.

Health Insurance Status

The household respondent was

asked if, between January 1, 1996, and the time of the Round 1 interview,

anyone in the family was covered by any of the sources of public

and private health insurance coverage discussed in the following

paragraphs. For this report, Medicare and CHAMPUS/CHAMPVA coverage

represent coverage as of the date of the Round 1 interview. (CHAMPUS

and CHAMPVA are the Civilian Health and Medical Programs for the

Uniformed Services and Veterans' Affairs.) All other sources of insurance

represent coverage at any time during the Round 1 reference period.

Persons counted as uninsured were uninsured throughout the Round

1 reference period. For additional details on health insurance status

measures in MEPS, see Vistnes and Monheit (1997).

Public Coverage

For this report, individuals

are considered to have public coverage only if they met both of the

following criteria:

-

They were

not covered by private insurance.

-

They were

covered by one of the following public programs: Medicare, Medicaid,

or other public hospital/physician coverage.

Private Health

Insurance

Private health insurance is

defined for this report as insurance that provides coverage for hospital

and physician care. Insurance that provides coverage for a single

service only, such as dental or vision coverage, is not counted.

Coverage by CHAMPUS/CHAMPVA is included as private health insurance.

Uninsured

The uninsured are defined

as persons not covered by Medicare, CHAMPUS/CHAMPVA, Medicaid, other

public hospital/physician programs, or private hospital/physician

insurance throughout the entire Round 1 reference period. Individuals

covered only by noncomprehensive State-specific programs (e.g., Maryland

Kidney Disease Program, Colorado Child Health Plan) or private single-service

plans (e.g., coverage for dental or vision care only, coverage for

accidents or specific diseases) are not considered to be insured.

Place of Residence

Individuals are identified

as residing either inside or outside a metropolitan statistical area

(MSA) as designated by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB),

which applied 1990 standards using population counts from the 1990

U.S. Census. An MSA is a large population nucleus combined with adjacent

communities that have a high degree of economic and social integration

with the nucleus. Each MSA has one or more central counties containing

the area's main population concentration. In New England, metropolitan

areas consist of cities and towns rather than whole counties. Regions

of residence are in accordance with the U.S. Bureau of the Census

definition and are determined as of the date of the Round 1 interview.

Additional

Cautions

Very few respondents named

emergency rooms as usual sources of care for members of their families.

As a result, the relative standard errors for many of the estimates

in the "Emergency room" column in Table

1 are quite high. Standard errors that are greater than or equal

to 30 percent of he estimate are indicated with an asterisk. Exact

relative standard errors can be calculated by dividing the appropriate

standard error, shown in Tables A-F, by the

estimate. Caution should be used in interpreting estimates in the "Emergency

room" column. They are presented for the benefit of those interested

in the use of emergency rooms as a usual source of health care, but

are best combined with the "Hospital outpatient department or

clinic" column.

As of the writing of this

report, population characteristics for MEPS are available only from

the first round of data collection. In contrast, the access-to-care

supplement was administered in Round 2. Population characteristics

may have changed between Rounds 1 and 2 for members of the MEPS panel,

so caution should be used in interpreting these data. This concern

is particularly applicable to health insurance status.

Sample

Design and Accuracy of Estimates

The sample selected for the

1996 MEPS, a subsample of the 1995 NHIS, was designed to produce

national estimates that are representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized

population of the United States. Round 1 data were obtained for approximately

9,400 households in MEPS, resulting in a survey response rate of

78 percent. This figure reflects participation in both NHIS and MEPS.

For Round 2, the response rate was 95 percent, resulting in a response

rate of 74 percent overall from the NHIS interview through Round

2 of MEPS.

The person-level estimates

presented in this report were derived from a nationally representative

sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized population defined as

of the first half of 1996. The estimates should be interpreted as

attributes of the target population defined as of the first half

of 1996. While the survey interviews that obtained data on access

to care were conducted in the second half of 1996, the questions

on access were not explicitly constrained by that time period.

The statistics presented in

this report are affected by both sampling error and sources of nonsampling

error, which include nonresponse bias, respondent reporting errors,

and interviewer effects. For a detailed description of the MEPS survey

design, the adopted sample design, and methods used to minimize sources

of nonsampling error, see J. Cohen (1997), S. Cohen (1997), and Cohen,

Monheit, Beauregard, et al. (1996). The MEPS person-level estimation

weights include nonresponse adjustments and poststratification adjustments

to population estimates derived from the March 1996 Current Population

Survey (CPS) based on cross-classifications by region, age, race/ethnicity,

and sex.

Tests of statistical significance

were used to determine whether the differences between populations

exist at specified levels of confidence or whether they occurred

by chance. Differences were tested using Z-scores having asymptotic

normal properties at the 0.05 level of significance. Unless otherwise

noted, only statistically significant differences between estimates

are discussed in the text. Rounding

Estimates presented in

the tables were rounded to the nearest 0.1 percent. Standard

errors were rounded to the nearest 0.01. Some of the estimates

for population totals of subgroups presented in the tables will

not add exactly to the overall estimated population total as

a consequence of rounding.

^top

^top

Standard Error Tables

Table A. Standard

errors for percent distribution of families with members

who changed

their

usual source of care in the past 12 months by reason for

change, United States, 1996

Corresponds to Figure 1

| Reason |

Standard

error |

| Insurance-related

reasons |

1.68

|

| Dissatisfied

with quality of care |

1.48

|

| Too

far away, moved to new area, or previous provider

not available |

1.68

|

| Other

reasons |

1.34

|

Note: Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table

B. Standard errors for percent distribution of persons by

type of office-based usual source of care, United States,

1996

Corresponds to Figure

2

| Type

of provider |

Standard

error |

| Family

practitioner/general practitioner |

0.97

|

| Internist/pediatrician |

0.70

|

| Other

medical specialist |

0.27

|

| Nonphysician

provider |

0.08

|

| Group

or clinic (no provider type identified) |

1.11

|

Note: Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table C. Standard

errors for percent distribution of population by usual source

of health care and selected population characteristics,

United States, 1996

Corresponds to Table

1

| Population

characteristics |

No

usual source of health care |

Usual

source of health care is: |

| Office-baseda |

Hospital

outpatient department or clinicb |

Emergency

room |

| Totalc |

0.43

|

0.60

|

0.46

|

0.07

|

| Age

in years |

| Under

6 |

0.64

|

1.14

|

0.96

|

0.25

|

| 6-17 |

0.67

|

0.91

|

0.68

|

0.11

|

| 18-24 |

1.27

|

1.39

|

0.71

|

0.34

|

| 25-54 |

0.59

|

0.70

|

0.49

|

0.08

|

| 55-64 |

0.86

|

1.38

|

1.15

|

0.22

|

| 65

and over |

0.71

|

1.11

|

0.90

|

0.15

|

| Race/ethnicity |

| Hispanic |

1.21

|

1.30

|

0.88

|

0.16

|

| Black |

0.95

|

1.34

|

1.11

|

0.41

|

| White

and other |

0.45

|

0.65

|

0.51

|

0.06

|

| Sex |

| Male |

0.54

|

0.71

|

0.48

|

0.08

|

| Female |

0.45

|

0.61

|

0.50

|

0.09

|

| Perceived

health status |

| Excellent |

0.65

|

0.87

|

0.58

|

0.09

|

| Very

good |

0.59

|

0.76

|

0.59

|

0.10

|

| Good |

0.74

|

0.95

|

0.64

|

0.18

|

| Fair |

1.01

|

1.33

|

0.97

|

0.25

|

| Poor |

1.22

|

1.86

|

1.46

|

0.53

|

| Health

insurance statusd |

| Under

age 65: |

| Any

private |

0.48

|

0.65

|

0.52

|

0.05

|

| Public

only |

0.98

|

1.61

|

1.23

|

0.38

|

| Uninsured |

1.10

|

1.23

|

0.75

|

0.27

|

| Age

65 and over: |

| Medicare

only |

1.47

|

2.01

|

1.58

|

0.32

|

| Medicare

and private |

0.81

|

1.27

|

1.06

|

0.17

|

| Medicare

and other public |

1.77

|

2.94

|

2.17

|

0.51

|

| Metropolitan

statistical area (MSA) |

| MSA |

0.50

|

0.68

|

0.49

|

0.08

|

| Non-MSA |

0.89

|

1.29

|

1.13

|

0.17

|

- aIncludes

all types of physicians and nonphysician providers seen

in an office setting as well as office-based group practices

or clinics.

- bIncludes

outpatient departments and clinics owned and operated by

hospitals.

- cIncludes

individuals with unknown health status and those few individuals

age 65 and over who do not have Medicare coverage. Excludes

a small number of persons who were eligible for data collection

in the first half of 1996 but died or were institutionalized

in the second half of the year. See Technical Appendix for

details.

- dThis

refers to health insurance status during the first half

of 1996. Uninsured refers to persons uninsured during the

entire period. Public and private insurance categories refer

to individuals with public or private insurance at any time

during the period; individuals with both public and private

insurance are considered privately insured. CHAMPUS and

CHAMPVA (Armed-Forces-related coverage) are considered private

health insurance in this report.

Note: Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Rounds 1 and 2).

^top

Table

D. Standard errors for percent of population by selected

characteristics of usual source of health care, United States,

1996

Corresponds to Table

2

| Characteristics

of usual source of care |

Standard

error for percent |

| Has

office hours at night or on weekends |

0.91

|

| Usually

have an appointment |

0.73

|

| Somewhat

difficult or very difficult to contact by telephone |

068

|

Note: Excludes

individuals whose usual source of care is an emergency room.

Restricted to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table

E. Standard errors for percent of population by satisfaction

with usual source of health care and continuity of care,

United States, 1996

Corresponds to Table

3

| Satisfaction

or continuity of care |

Standard

error for percent |

| Somewhat

satisfied or very satisfied with overall quality of

care |

0.20

|

| Somewhat

satisfied or very satisfied with professional staff |

0.26

|

| Provider

generally listens to them and gives them needed health

information |

0.25

|

| Confident

in provider's ability to help with a medical problem |

0.25

|

| Provider

usually asks about prescription medications and treatments

from other doctors |

0.67

|

Note: Excludes

individuals whose usual source of care is an emergency room.

Restricted to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Round 2).

^top

Table

F. Standard errors for percent of families with members

experiencing difficulty or delay or not receiving needed

health care by main problem in receiving care and family

characteristics, United States, 1996

Corresponds to Table

4

| Family

characteristics |

Any

problem |

Main

problem |

| Inability

to afford care |

Insurance-related

reasonsa |

Other

problemsb |

| Total |

0.40

|

1.84

|

1.33

|

1.31

|

| Race/ethnicity

of head of family |

| Hispanic |

1.26

|

3.96

|

3.00

|

2.87

|

| Black |

0.92

|

5.29

|

2.84

|

4.33

|

| White

and other |

0.45

|

2.06

|

1.57

|

1.52

|

| Perceived

health statusc |

| Any

family member in fair or poor health |

1.00

|

2.84

|

1.96

|

2.19

|

| All

family members in excellent,very good,or good health |

0.40

|

2.14

|

1.63

|

1.61

|

| Health

insurance status of familyd |

| All

members private insurance |

0.35

|

2.38

|

2.20

|

2.31

|

| All

members public insurance |

1.20

|

5.85

|

5.11

|

4.56

|

| All

members uninsured |

1.67

|

2.30

|

1.49

|

1.69

|

| Some

private, some uninsured |

1.75

|

4.39

|

3.17

|

2.64

|

| Some

public, some uninsured |

2.18

|

4.35

|

1.47

|

4.18

|

| Some

private, some public |

1.83

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

| Some

private, some public,some uninsured |

4.87

|

--

|

--

|

--

|

| Metropolitan

statistical area (MSA) |

| MSA |

0.44

|

2.11

|

1.55

|

1.44

|

| Non-MSA |

0.84

|

3.56

|

2.62

|

3.07

|

- aIncludes

insurance company wouldn't approve, cover, or pay for care;

pre-existing condition; insurance required a referral but

couldn't get one; doctor refused to accept family's insurance

plan.

- bIncludes

transportation problems (medical care was too far away,

can't drive or don't have car/no public transportation available,

too expensive to get there); physical problems (hard to

get into building, hard to get around inside building, no

appropriate equipment in office); communication problems

(hearing impairment or loss, different language); and other

problems (couldn't get time off work, didn't know where

to go to get care, was refused services, couldn't get child

care, didn't have time or took too long).

- cA

small number of families with missing health status for

all family members are excluded from this breakdown but

included in the total line of the table. See Technical Appendix

for details.

- dRefers

to health insurance status during the first half of 1996.

Uninsured refers to persons uninsured during the entire

period. The public and private insurance categories refer

to individuals with public or private insurance at any time

during the period; individuals with both publicand private

insurance are considered privately insured. CHAMPUS and

CHAMPVA (Armed-Forces-related coverage) are considered private

health insurance in this report.

- Sample sizes are

too small to support reliable estimation.

Note: Restricted

to civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Rounds 1 and 2).

^top

Suggested Citation:

Weinick,

R. M., Zuvekas, S. H., and Drilea, S. Research

Findings #3: Access to Health Care - Sources

and Barriers,

1996. February 2006. Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality, Rockville, MD.

http://www.meps.ahrq.gov

/data_files/rf3.shtml

|

|