Chartbook #8:

Disparities and Gender Gaps in Women’s Health, 1996

By Barbara L. Kass-Bartelmes, M.P.H., C.H.E., Barbara M.Altman, Ph.D., Amy K.Taylor, Ph.D.

Contents

The estimates in this report are based on the most recent data available from MEPS at the time the report was written. However, selected elements of MEPS data may be revised on the basis of additional analyses, which could result in slightly different estimates from those shown here. Please check the MEPS Web site for the most current file releases — www.meps.ahrq.gov

AHRQ is the lead Federal agency charged with supporting research designed to improve the quality of health care, reduce its cost, address patient safety and medical errors, and broaden access to essential services. AHRQ sponsors and conducts research that provides evidence-based information on health care outcomes; quality; and cost, use, and access. The information helps health care decision makers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers—make more informed decisions and improve the quality of health care services.

Executive Summary

This report presents estimates of health insurance, access to care and use of care, and health status among women of different ages and racial/ethnic groups in America, as well as differences between men and women. Key findings include:

Health insurance

Hispanic women were more likely than women in any other racial/ethnic group to be uninsured in 1996.

Medicaid enrollment for women increased from 1987 to 1996.

Higher proportions of women than men were covered by Medicaid in both 1987 and 1996.

Access to and use of care

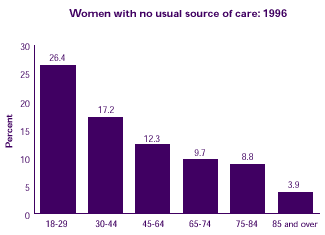

Women ages 18-29 were less likely than women in any other age group to have a usual source of care in 1996.

In 1996, women’s total health care expenses were higher than men’s for ambulatory care, prescription medicines, and home health services.

In 1996, black women were more likely than women from any other racial/ethnic group to have had a Pap smear or complete physical exam within the past 2 years.

Health status

The majority of women in America were in excellent, very good, or good health in 1996.

Women were more likely than men in 1996 to have functional limitations.

Hispanic and black women were more likely than white women to be in fair or poor health during 1996.

Return To Table Of Contents

Introduction

Eliminating inequities in health and health care while promoting the prevention of disease and disability in America's women requires that women have adequate access to medical care. Gaps in health insurance status still exist between men and women, as do gaps in the use of health services between females in different racial/ethnic groups. Education and income are important factors that influence a woman's health status.

This report focuses on three key aspects of women's health. The first section introduces data on health insurance status for women as compared to men and describes racial/ethnic differences among women. The second section presents information on access to care and use of medical services, including gender differences and racial/ethnic differences among women for usual source of care, use of care, and preventive services. Finally, the third section depicts women's health status, including functional limitations. It compares men and women, as well as women of different racial/ethnic groups, income levels, and educational status.

Return To Table Of Contents

Source of Data for This Report

The estimates presented in this report are drawn from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES) and the Household Component of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). MEPS is the third in a series of medical expenditure surveys conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It is a nationally representative survey that collects detailed information on health status, health care use and expenses, and health insurance coverage of individuals and families in the United States.

The estimates presented here are nationally representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized population age 18 and over. Charts that are for only part of the adult population—such as workers age 19 and over, people age 65 and over, or people ages 18-64—are labeled to show which groups are included. All other charts are for adults age 18 and over.

MEPS data are released to the public in a number of formats, including public use data files and the printed MEPS Research Findings and MEPS Highlights series. The numbers shown in this chartbook are drawn from a variety of the Research Findings reports as well as additional analyses conducted by the MEPS staff. Specific sources for the information presented here are listed in the references section.

In some cases, totals may not add precisely to 100% as a consequence of rounding. The category "other," used in charts depicting racial/ethnic differences, includes a number of individuals identified as Asians, American Indians, Aleuts, Eskimos, or other races. The health of these groups is of interest, but MEPS includes too few individuals to present data on them separately. Only differences that are statistically significant at the 0.05 level are discussed in the text.

Return To Table Of Contents

Section 1: Health Insurance

Although the majority of women in America had either public or private insurance in 1996, gender as well as racial/ethnic disparities continued to exist. The health insurance data presented here come from the 1996 MEPS and the 1987 NMES. Private health insurance was defined as insurance that provides coverage for hospital and physician care, including Medigap coverage but not including single-service coverage such as dental or vision insurance. The public health insurance category includes people who were not covered by private insurance but were covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or other public hospital/physician coverage. See Note 1 for information on health insurance data collection.

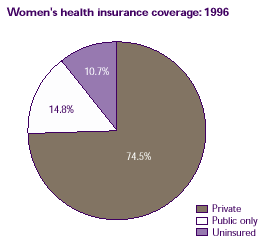

Overall, what is the health insurance status of American women?

In 1996, the majority of women age 18 and over (nearly 75%) had private insurance, another 14.8% had public insurance only, and 10.7% were uninsured.

|

Women's health insurance

coverage: 1996 |

| Private |

74.5% |

| Public only |

14.8% |

| Uninsured |

10.7% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

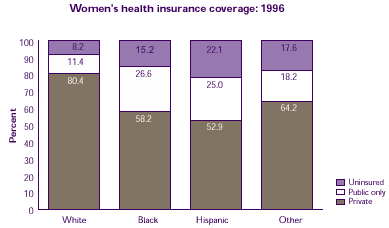

Does women's health insurance status differ among racial/ethnic groups?

- In 1996, over three-fourths of white women had private health insurance, compared to about half of black or Hispanic women.

- White women were the least likely of all racial/ethnic groups to have public insurance.

- Hispanic women were the most likely to be uninsured.

|

| Women's health insurance coverage: 1996 |

| |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Other |

| Private |

80.4% |

58.2% |

52.9% |

64.2% |

| Public only |

11.4% |

26.6% |

25.0% |

18.2% |

| Uninsured |

8.2% |

15.2% |

22.1% |

17.6% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

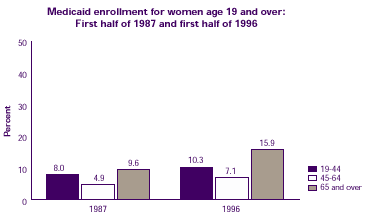

How has Medicaid enrollment among women changed from 1987 to 1996?

- Overall, the percent of women enrolled in Medicaid increased for all age groups from 1987 to 1996.

- Women age 65 and over were the age group most likely to be enrolled in Medicaid.

|

| Medicaid enrollment for women age 19 and over: First half of 1987 and first half of 1996 |

| |

19-44 |

45-64 |

65 and over |

| 1987 |

8.0% |

4.9% |

9.6% |

| 1996 |

10.3% |

7.1% |

15.9% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

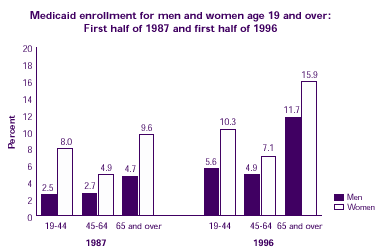

How has Medicaid coverage changed for men and women changed from 1987 to 1996?

- Among all age groups, a higher proportion of women than men were covered by Medicaid in both years.

- The percent of both men and women enrolled in Medicaid increased from 1987 to 1996.

- Medicaid coverage increased by 6.3 percentage points for elderly women and 7.0 percentage points for elderly men.

|

| Medicaid enrollment for men and women age 19 and over: First half of 1987 and first half of 1996 |

| |

19-44 |

45-64 |

65 and over |

| 1987 - Men |

2.5% |

2.7% |

4.7% |

| 1987 - Women |

8.0% |

4.9% |

9.6% |

| 1996 - Men |

5.6% |

4.9% |

11.7% |

| 1996 - Women |

10.3% |

7.1% |

15.9% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

Section 2: Access and Use of Care

One measure of access to care is whether or not people have a usual source of care—a person or place they usually go to if they are sick or need advice about their health. Use of health services can also serve as an assessment of access. Health insurance, income, and education are all factors that have been associated with a person's access to health care. Other factors that may influence access to care include availability of providers, facilities, and transportation.

This section describes women's usual source of care and use of services. Comparisons are made with access and use for men and among women of different racial/ethnic groups.

Does access to care vary by women's age?

Women ages 18-29 were more likely than women in any other age group to lack a usual source of care, while women age 85 and over were the least likely to be without a usual source of care.

|

Women with no usual

source of care: 1996 |

| 18-29 |

26.4% |

| 30-44 |

17.2% |

| 45-64 |

12.3% |

| 65-74 |

9.7% |

| 75-84 |

8.8% |

| 85 and over |

3.9% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

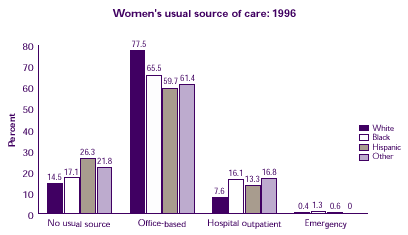

Does the usual source of care for women vary by race/ethnicity?

- Hispanic women were less likely than white or black women to have a usual source of care during 1996.

- White women were the most likely to have an office-based source of health care.

|

| Women's usual source of care: 1996 |

| |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Other |

| No usual source |

14.5% |

17.1% |

26.3% |

21.8% |

| Office-based |

77.5% |

65.5% |

59.7% |

61.4% |

| Hospital outpatient |

7.6% |

16.1% |

13.3% |

16.8% |

| Emergency |

0.4% |

1.3% |

0.6% |

0% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

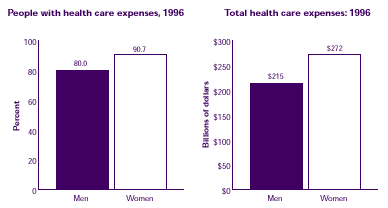

Are health care expenses different for men and women?

- Women were more likely than men to have health care expenses in 1996 (90.7% compared to 80.0%).

- Women's total health care expenses in 1996 totaled about $272 billion, compared to only about $215 billion for men.

|

| People with health care expenses, 1996 |

| Men |

80.0% |

| Women |

90.7% |

|

| Total health care expenses: 1996 |

| Men |

$215 |

| Women |

$272 |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

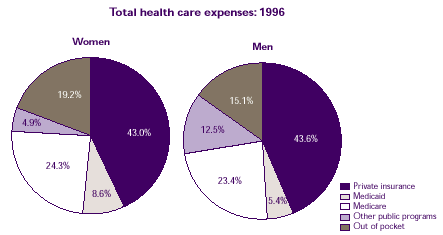

Are payment sources different for men's and women's health care?

- The distribution of total health care expenses by source of payment was similar for women and men, although women paid a higher percent out of pocket than men (19.2% vs. 15.1%).

- About 12.5% of men's total expenses were paid by public programs other than Medicare and Medicaid, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs. This "other public programs" category covered only 4.9% of expenses for women.

See Note 2 for definitions of payment sources.

|

| Total health care expenses: 1996 |

| |

Women |

Men |

| Private insurance |

43.0% |

43.6% |

| Medicaid |

8.6% |

5.4% |

| Medicare |

24.3% |

23.4% |

| Other public programs |

4.9% |

12.5% |

| Out of pocket |

19.2% |

15.1% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

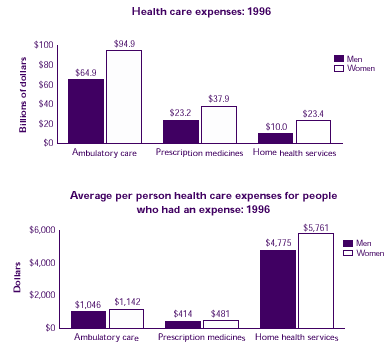

Which health care services cost more for women than for men?

- Expenses for ambulatory care were higher for women ($94.9 billion) than they were for men ($64.9 billion). (See Note 3.)

- Women had higher expenses than men for prescription medicines ($37.9 billion compared to $23.2 billion) and for home health services ($23.4 billion compared to $10.0 billion). (See Note 4.) Although women were more likely than men to use these services, women's average expenses per person for ambulatory care and home health services were not significantly different from men's expenses. Women did, however, have higher prescription drug expenses than men.

|

| Health care expenses: 1996 |

| |

Men |

Women |

| Ambulatory care |

$64.9 |

$94.9 |

| Prescription medicines |

$23.2 |

$37.9 |

| Home health services |

$10.0 |

$23.4 |

| Billions of dollars |

|

| Average per person health

care expenses for people

who had an expense: 1996 |

| |

Men |

Women |

| Ambulatory care |

$1,046 |

$1,142 |

| Prescription medicines |

$414 |

$481 |

| Home health services |

$4,775 |

$5,761 |

| Dollars |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

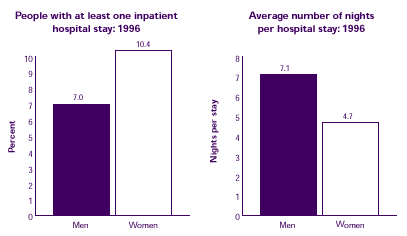

Does inpatient hospitalization differ for men and women?

A higher percentage of women than men were hospitalized in 1996. However, among those with hospital stays, men were hospitalized longer than women.

|

| People with at least one inpatient

hospital stay: 1996 |

| Men |

Women |

| 7.0% |

10.4% |

|

| Average number of nights per

hospital stay: 1996 |

| Men |

Women |

| 7.1 |

4.7 |

| Nights per stay |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

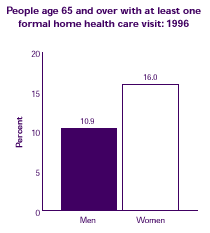

Is use of home health services different for men and women?

Elderly women were more likely than elderly men to have at least one formal home health care visit in 1996.

|

People age 65 and over with

at least one formal home

health care visit: 1996 |

| Men |

Women |

| 10.9% |

16.0% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

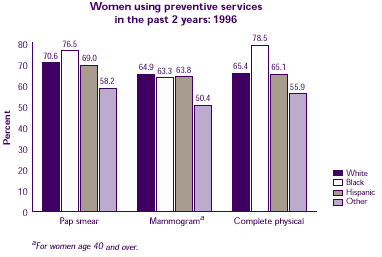

How does women's use of preventive services differ among racial/ethnic groups?

- Black women were more likely to have had a Pap smear or a complete physical exam within the past 2 years than women in any other racial/ethnic category.

- Women of other racial/ethnic groups were the least likely to have had a mammogram within the past 2 years.

|

| Women using preventive services in the past 2 years: 1996 |

| |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Other |

| Pap smear |

70.6% |

76.5% |

69.0% |

58.2% |

| Mammograma |

64.9% |

63.3% |

63.8% |

50.4% |

| Complete physical |

65.4% |

78.5% |

65.1% |

55.9% |

| aFor women age 40 and over |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

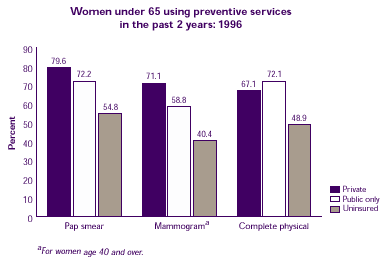

What influence does health insurance have on women's use of preventive health services?

Women under age 65 who had either private or public health insurance were more likely than uninsured women to have a Pap smear, a mammogram, or a complete physical examination within the past 2 years.

|

| Women under 65 using preventive services in the past 2 years: 1996 |

| |

Private |

Public |

Uninsured |

| Pap smear |

79.6% |

72.2% |

54.8% |

| Mammograma |

71.1% |

58.8% |

40.4% |

| Complete physical |

67.1% |

72.1% |

48.9% |

| aFor women age 40 and over |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

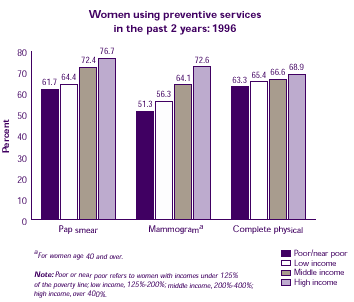

Is income associated with women's use of preventive health services?

Women with higher incomes (who often have more education) were more likely to have a Pap smear or mammogram within the past 2 years.

|

| Women using preventive services in the past 2 years: 1996 |

| |

Poor/near poor |

Low income |

Middle income |

High income |

| Pap smear |

61.7% |

64.4% |

72.4% |

76.7% |

| Mammograma |

51.3% |

56.3% |

64.1% |

72.6% |

| Complete physical |

63.3% |

65.4% |

66.6% |

68.9% |

aFor women age 40 and over

Note: Poor or near poor refers to women with incomes under 125% of the poverty line; low income, 125%-200%; middle income, 200%-400%; high income, over 400%. |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

Section 3: Health Status

Health status is measured by asking the question, "Would you rate this person's health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?" This section shows gender differences in health status and differences among women according to various characteristics.

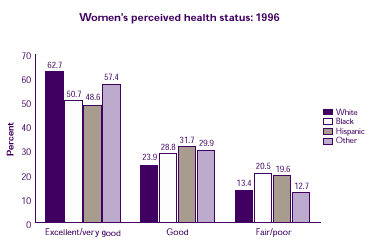

Is health status different for women in various racial/ethnic groups?

In 1996, Hispanic and black women were more likely than white women to be in fair or poor health. Overall, however, the majority of women of all racial/ethnic groups were in excellent, very good, or good health.

|

| Women's perceived health status: 1996 |

| |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Other |

| Excellent/very good |

62.7% |

50.7% |

48.6% |

57.4% |

| Good |

23.9% |

28.8% |

31.7% |

29.9% |

| Fair/Poor |

13.4% |

20.5% |

19.6% |

12.7% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

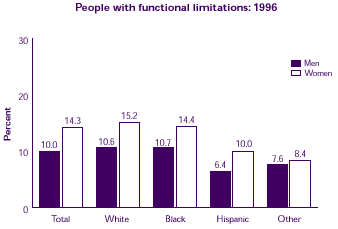

Do women have more functional limitations than men have?

Overall, more women than men had functional limitations. White, black, and Hispanic women were significantly more likely than their male counterparts to report having any functional limitations. Functional limitations include difficulties walking, climbing stairs, grasping objects, reaching overhead, lifting, bending or stooping, or standing for long periods of time.

|

| People with functional limitations: 1996 |

| |

Total |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

Other |

| Men |

10.0% |

10.6% |

10.7% |

6.4% |

7.6% |

| Women |

14.3% |

15.2% |

14.4% |

10.0% |

8.4% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

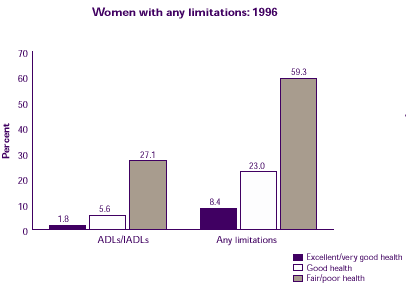

How are limitations related to health status for women?

- Women in fair or poor health were more likely than women in excellent, very good, or good health to have difficulty with activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). (See Note 5 for definitions of ADLs and IADLs.)

- Women in fair or poor health were also more likely to have any functional limitations or any activity limitations. (See Note 6.)

|

| Women with any limitations: 1996 |

| |

ADLs/

IADLs |

Any limitations |

| Excellent/very good health |

1.8% |

8.4% |

| Good health |

5.6% |

23.0% |

| Fair/Poor health |

27.1% |

59.3% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

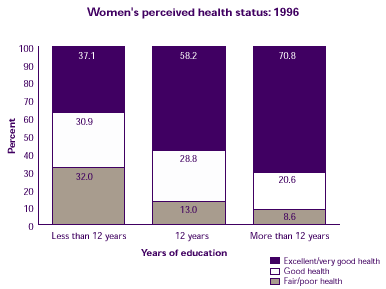

How is education associated with health status?

- Women with more than 12 years of education were the most likely to be in excellent or very good health.

- Women with less than 12 years of education were the most likely to be in fair or poor health.

|

| Women's perceived health status: 1996 |

| |

Less than 12 years |

12 years |

More than 12 years |

| Excellent/very good health |

37.1% |

58.2% |

70.8% |

| Good health |

30.9% |

28.8% |

20.6% |

| Fair/Poor health |

32.0% |

13.0% |

8.6% |

| Years of education |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

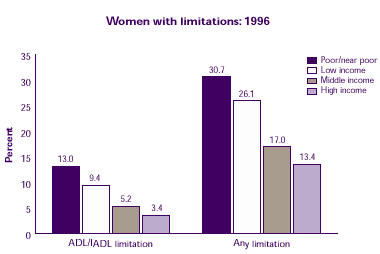

How is income related to limitations?

Women who were poor or near poor were more likely than women in any of the higher income categories to have ADL or IADL limitations, activity limitations, or functional limitations.

|

| Women with limitations: 1996 |

| |

Poor/near poor |

Low income |

Middle income |

High income |

| ADL/IADL Limitation |

13.0% |

9.4% |

5.2% |

3.4% |

| Any Limitations |

30.7% |

26.1% |

17.0% |

13.4% |

|

Return To Table Of Contents

Conclusions

The data presented in this report show that women:

- Increased their Medicaid enrollment from 1987 to 1996.

- Represented a higher proportion covered by Medicaid both in 1987 and 1996 compared to men.

- Used more health services than men in 1996.

- Had more functional limitations than men in 1996.

When women are compared by racial/ethnic and income groups, the data show that:

- Black and Hispanic women were less likely than white women to have private insurance, and Hispanic women were the most likely of all racial/ethnic groups to be uninsured in 1996.

- Hispanic women were less likely than black or white women to have a usual source of care.

- Black and Hispanic women were more likely than white women to be in poor or fair health.

- Women with higher incomes were the most likely to use preventive services and the least likely to have functional limitations.

Return To Table Of Contents

Looking Ahead: Future MEPS Data

This report presents estimates of health insurance coverage, access to health care, and health status. Future data from MEPS will address additional aspects of health care, including:

- Quality of care and burden of disease.

- Patient/customer satisfaction.

- The impact of managed care.

- Use of specific services.

- Additional measures of health status, including health conditions and functional limitations.

- Amounts families pay for private health insurance coverage.

MEPS is a unique data resource for monitoring our Nation's health care system. As an ongoing survey, MEPS produces data that can be used to examine changes over time.

Return To Table Of Contents

References

The following references served as source material for this chartbook.

Altman BM, Taylor AK. Women in the health care system: health status, insurance, and access to care. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; to be published. MEPS Research Findings No. 17. AHRQ Pub. No. 02-0004.

Banthin JS, Cohen JW. Changes in the Medicaid community population: 1987-96. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. MEPS Research Findings No. 9. AHCPR Pub. No. 99-0042.

Cohen JW, Machlin SR, Zuvekas SH, et al. Health care expenses in the United States, 1996. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2000. MEPS Research Findings No. 12. AHRQ Pub. No. 01-0009.

Krauss NA, Machlin S, Kass BL. Use of health care services, 1996. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999. MEPS Research Findings No. 7. AHCPR Pub. No. 99-0018.

Vistnes JP, Monheit AC. Health insurance status of the civilian noninstitutionalized population: 1996. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research; 1997. MEPS Research Findings No. 1. AHCPR Pub. No. 97-0030.

Return To Table Of Contents

Notes

Note 1: Unless otherwise noted, information on health insurance status refers to the first half of 1996. The household respondent was asked anyone in the family was covered by any sources of public and private health insurance coverage during that time. For additional details on health insurance status measures in MEPS, see Altman and Taylor (to be published) and Vistnes and Monheit (1997).

Note 2: Private insurance includes CHAMPUS and CHAMPVA (Armed-Forces-related coverage). Other public programs include Department of Veterans Affairs (except CHAMPVA); other Federal sources (Indian Health Service, military treatment facilities, and other care provided by the Federal Government); other State and local sources (community and neighborhood clinics, State and local health departments, and State programs other than Medicaid); other public (Medicaid payments reported for persons who were not enrolled in the Medicaid program at any time during the year);Worker's Compensation; other unclassified sources (e.g., automobile, homeowner's, liability, and other miscellaneous or unknown sources); and other private insurance (any type of private insurance payments reported for persons without private health insurance coverage during the year, as defined in MEPS).

Note 3: Ambulatory care includes visits to medical providers seen in office-based settings or clinics, hospital outpatient departments, emergency rooms (except visits resulting in an overnight hospital stay), and clinics owned and operated by hospitals. It also includes events reported as hospital admissions without an overnight stay.

Note 4: Home health care is defined as any agency-sponsored or paid independent home health care provider.

Note 5: ADLs are activities of daily living, including personal care such as bathing, dressing, or getting around the house. IADLs are instrumental activities of daily living such as using the telephone, paying bills, taking medications, preparing light meals, doing laundry, or going shopping.

Note 6: The measure "any limitations" is a combined measure that indicates whether an individual had one or more limitations, including ADLs/IADLs, physical activity limitations (such as difficulties walking, bending, or stooping), or work/housework/school limitations. It also included other limitations in social role behavior and cognitive limitations. See Altman and Taylor (to be published).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Tommy G. Thompson, Secretary

Office of Public Health and Science

David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., Surgeon General of the United States

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

John M. Eisenberg, M.D., M.B.A., Director

Return To Table Of Contents

| Suggested Citation: Chartbook #8: Disparities and Gender Gaps in Womens Health, 1996. November 2001. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/cb8/cb8.shtml |

|