Research

Findings #13: Expenses and Sources of Payment for Nursing Home Residents,

1996

by Jeffrey Rhoades, Ph.D., and John Sommers,

Ph.D., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Abstract This report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality presents estimates of total nursing home expenses during 1996. Data are derived from the 1996 Nursing Home Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Separate estimates are presented for mean expenses per person and per day. The distribution of sources of payment is shown by demographic, financial, and health status characteristics of nursing home users. Differences in expenses by selected personal characteristics are discussed. Expenses for different types of nursing homes are also shown. In 1996, Medicaid contributed 44 percent to total annual nursing home expenditures, Medicare contributed 19 percent, and out-of-pocket payments contributed 30 percent. People with the shortest nursing home stays had the highest annual expenses per patient day.

Introduction

Data pertaining

to the nursing home industry are of critical importance

because of the dramatic growth

in the number of Americans over age 75 and the desire to minimize

the duration of expensive inpatient hospital care. The trend

in long-term care is toward expansion of community-based care

for people with functional limitations. However, there continues

to be a subset of individuals who need sophisticated 24-hour

skilled nursing supervision. A better understanding of the

current nursing home market can contribute to informed decisions

about the provision of long-term care.

National expenses for services in nursing

homes amounted to about $70 billion in 1996, according to

data from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)

Nursing Home Component (NHC).1 Thirty

percent of the total was paid out of pocket from Social Security

or pension income or from other income or assets of the sample

person or sample person's family. A small amount (4 percent)

was paid for through private insurance. The Medicaid program

financed most of the remainder (44 percent), Medicare paid

19 percent, and 3 percent of expenditures were paid by other

sources (Department of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance

organization contract, or other). Because most nursing home

care is financed out of pocket or through Medicaid, the prospect

of rapid increases in the number of Americans who are elderly

and at risk for nursing home care has turned the financing

of these services into a matter of intense private and public

concern. State and Federal Medicaid budgets will be stretched

to cover nursing home services for those who cannot afford

this type of care.

The 1996 MEPS NHC, conducted by the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), was a national,

year-long panel survey of nursing homes and their residents

designed to provide estimates of expenses and sources of payment

for all people using nursing homes at any time in 1996. MEPS

is the third in a series of AHRQ-sponsored surveys to collect

information on the health care use and spending of the American

public. The first survey was the 1977 National Medical Care

Expenditure Survey (NMCES), and the second was the 1987 National

Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES). NMES was the first national

expenditure survey to contain an institutional component designed

explicitly to collect detailed medical expense information

on people in long-term care facilities (Potter, 1998).

The estimates

reported here describe the distribution and rates of spending

over the course of a calendar

year from a variety of perspectives for nursing homes and

their residents. First, all people who used a nursing home

during 1996 that is, the people who account for 1996 nursing

home expenses were categorized with respect to their institutional

experience over the course of the year. Those who were institutionalized

all year are distinguished from 1996 admissions, and those

alive at the end of 1996 are distinguished from those who

died in 1996. These distinctions take into account the fact

that people who stayed in a nursing home during the entire

12-month reference period were long-stay patients, but 1996

admissions also include a heavy representation of patients

who were in the nursing home for relatively short periods

of time (often less than 3 months). A more detailed discussion

is provided in the section "Type of Stay."

Previous research has shown that long-stay

and short-stay patients are significantly different in health

status, sociodemographic characteristics, and use and expense

patterns (Dunkle and Kart, 1990; Kemper, Spillman, and Murtaugh,

1991; Spence and Wiener, 1990; Wayne, Rhyen, Thompson, et

al., 1991). Average annual expenses in 1996, annual out-of-pocket

expenses, average daily expenses, and the share of expenses

paid by various third-party sources vary across subgroups

defined by their institutional experience and vital status

at the end of the year. There is also substantial variation

in expense patterns according to the demographic characteristics,

income, and health status of nursing home residents.

To shed light on variations in nursing

home expenses, this report describes average daily nursing

home expenses classified by payment source, geographic location,

and type of facility.

The technical appendix presents details

concerning sample selection, the sources of data, and questionnaire

items, and explains how the estimates were derived. It also

provides information on the construction of variables used

in the analysis and on estimates of standard errors for assessing

the confidence level of the national estimates. Definitions

of terms used in this report are also included. Except as

indicated, only statistically significant differences between

estimates are discussed in the text.

^top

Type of Stay

Resident on January 1, 1996

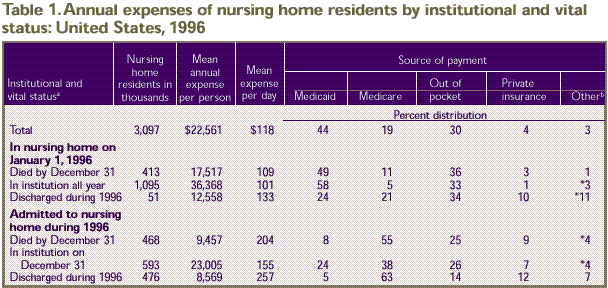

Over one-third of nursing home residents

(1,095,000) were in a nursing home at the beginning of the

year and remained institutionalized through December 31, 1996 (Table

1). Expenses for these residents amounted to $36,368 per

person for the year, or $101 per nursing home day. (This annual

estimate includes fewer than 366 nursing home days for some

full-year nursing home residents with short-term hospital

stays.) Medicaid financed 58 percent of expenses for this

group; 33 percent was paid out of pocket. In addition, 413,000

people residing in nursing homes at the beginning of 1996

had died by the end of the year. Their 1996 average expenses

($17,517) were less than half the expenses of those who survived

in a nursing home beyond 1996. Their average expense per day

($109) was greater and their reliance on Medicaid (49 percent)

as a source of payment was less when compared to full-year

residents.

Admitted During 1996

Of residents admitted to nursing homes

in 1996, 593,000 people remained institutionalized beyond

the end of the year. Their average expense per day ($155)

was higher than the expense for full-year residents. The share

of their annual expense paid out of pocket (26 percent) was

similar to the average for all residents (30 percent), while

the share paid by Medicaid was lower (24 percent, compared

to 44 percent for all nursing home residents). Another 468,000

people admitted in 1996 had died by the end of the year. Their

average daily expense ($204) was higher than the average for

all nursing home users ($118), and the proportion paid by

Medicaid was considerably lower (8 percent) than for full-year

residents. A relatively large share was paid by Medicare (55

percent), and 25 percent was paid out of pocket.

Most of the

527,000 nursing home users who were discharged to the community

during 1996 were part

of the 1996 admissions cohort (476,000). The average daily

nursing home expenses for those admitted and discharged during

the year were high—$257. At $8,569, their annual nursing

home expenses were less than half the average ($22,561), indicating

a shorter nursing home stay. In 1996 such individuals averaged

a length of stay of just 33 days, compared to an average stay

of 191 days for the total nursing home population (data not

shown). The high daily expenses could reflect, in part, an

increased intensity and concentration of nursing home services.

The majority of the expenses for this group (63 percent) were

paid for by Medicare. The Medicare share was similar to that

for the 1996 admissions who had died by the end of the year

(55 percent). Medicaid coverage (5 percent) was virtually

the same as that for 1996 admissions who had died by the end

of the year (8 percent). Private health insurance paid for

12 percent of nursing home expenses for residents admitted

and discharged during the year.

In percentage terms (derived from Table

1), 35 percent of nursing home users were institutionalized

all year and 13 percent died during 1996 after beginning

the year in a nursing home. Nineteen percent of the total

nursing home population were admitted in 1996 and survived

beyond the end of the year, and 15 percent of the total

were admitted in 1996 and had died by the end of the year.

The remainder of the nursing home population (17%) were

discharged during the year.

^top

Characteristics

of Residents

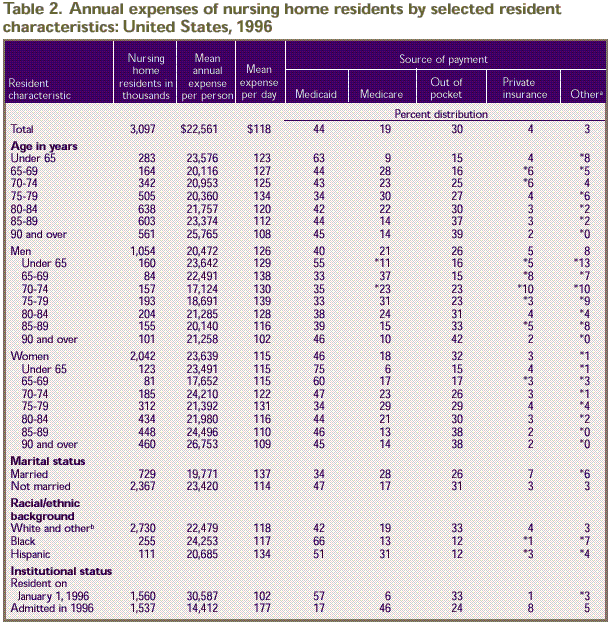

The variation in expenses and sources

of payment across subgroups of nursing home residents is only

partly explained by differences in institutional status over

the year. Tables 2–4 show

variation by other nursing home resident characteristics.

Annual nursing home expenses, except those for people under

65, tended to increase with increasing age, while the average

expense per nursing home day tended to decrease. Higher annual

expenses coupled with lower daily expenses for older residents

indicates that nursing home stays were longer for such residents (Table

2). In 1996 the average length of stay ranged from 158

days for residents ages 65–69 to 239 days for those 90

and over (data not shown). In addition, nursing home care

was possibly of a more custodial nature as the age of the

nursing home resident increased. Women age 85 and over were

the age-sex group most likely to be institutionalized all

year (data not shown), but compared with women under age 70,

a smaller share of their expenditures was financed by Medicaid

and a larger share was paid out of pocket.

Demographic Characteristics

In general, the proportion of expenses

paid for by the different sources of payment varied more with

age than annual and daily expenses did (Table

2). Women were more likely than men to have longer stays

in 1996 (206 and 163 days, respectively; data not shown).

This is reflected in women's annual expenses, which were substantially

higher ($23,639 vs. $20,472), while their daily expenses were

lower than those for men ($115 vs. $126). Lower daily expenses

for women may also indicate that women received a less concentrated

delivery of nursing home services than men. The share of expenditures

paid by Medicare was similar for women and men. In contrast,

women paid a greater proportion of their expenses with Medicaid

and out-of-pocket sources of payment

The expenses of married residents averaged

$137 per day, compared to $114 for unmarried residents. However,

married residents averaged $19,771 in annual expenses (in

contrast to $23,420 for unmarried residents) because married

residents tended to have shorter stays in 1996 (144 days,

as opposed to 205 days for unmarried residents). The higher

daily expense for married residents could also be a function

of a greater intensity in the use of nursing home services.

Thirty-four percent of the expenses of married residents were

paid for by Medicaid, compared to 47 percent for the unmarried.

In contrast, married residents relied to a greater extent

on Medicare (28 percent) and private insurance (7 percent)

when compared to unmarried users (17 and 3 percent, respectively).

Sources of payment varied with respect

to race and ethnicity, although there were no differences

in annual or daily expenses by racial/ethnic groups. Whites

and others (others are included with whites because of small

sample size) paid for 33 percent of their nursing home expenses

out of pocket. Blacks and Hispanics both paid 12 percent of

their expenses out of pocket.

Annual expenses, daily expense, and sources

of payment varied by institutional status. People residing

in a nursing home on January 1, 1996, had greater annual expenses

than those admitted during the year ($30,587 vs. $14,412)

and lower daily expenses ($102 vs. $177), and they relied

more heavily on Medicaid (57 percent vs. 17 percent) and out

of pocket (33 percent vs. 24 percent) as sources of payment.

Nursing home residents admitted in 1996 had a greater proportion

of their nursing home bill paid for by Medicare than continuing

residents had (46 percent compared to 6 percent) and also

relied more on private insurance (8 percent compared to 1

percent).

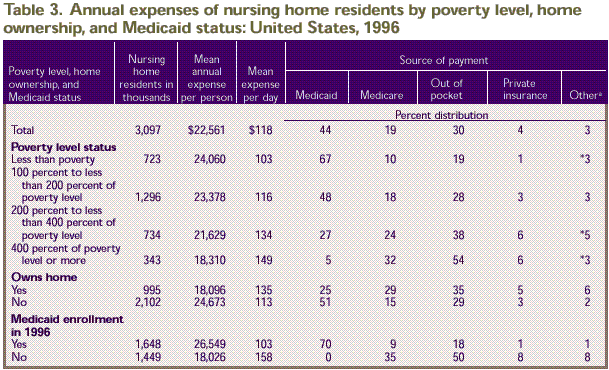

Poverty Level, Home Ownership, and Medicaid

Status

Average expenses per day increased

with annual income, from $103 per day in the lowest income group

to $149 in the highest income group (Table 3).

Annual expenses exhibited just the opposite pattern, decreasing

from $24,060 for the lowest income group to $18,310 for the highest

income group. The share of expenses paid out of pocket increased

with income. Medicaid paid 67 percent of 1996 nursing home expenses

for the lowest income group, compared to just 5 percent for nursing

home residents with incomes of four times or more the poverty

level. While the Medicaid share of expenses for people in the

lowest income group was substantial, they still paid for 19 percent

of nursing home expenses out of pocket.

Residents who owned a home at the date

of interview had lower annual but higher daily expenses than

those who did not own a home. Home owners had annual expenses

of $18,096 and daily expenses of $135, compared to $24,673

and $113, respectively, for residents who were not home owners.

Sources of payment also varied by home ownership. Home owners

paid a greater proportion of their expenses through Medicare

(29 percent vs. 15 percent) and out of pocket (35 percent

vs. 29 percent) and relied less on Medicaid (25 percent vs.

51 percent) than residents who did not own a home.

Medicaid enrollees averaged more in annual

nursing home expenses than people not on Medicaid ($26,549

per year vs. $18,026) but had a lower daily expenditure rate

($103 vs. $158). Residents without Medicaid support paid 50

percent of their expenses out of pocket, for an average of

$9,013 per person for the year. Those enrolled in Medicaid

at some point in 1996 paid 18 percent of their own expenses

($4,779). In addition to paying more out of pocket, residents

without Medicaid relied more heavily on Medicare (35 percent

vs. 9 percent for Medicaid enrollees), private insurance (8

percent vs. 1 percent), and other sources of payment (8 percent

vs. 1 percent).

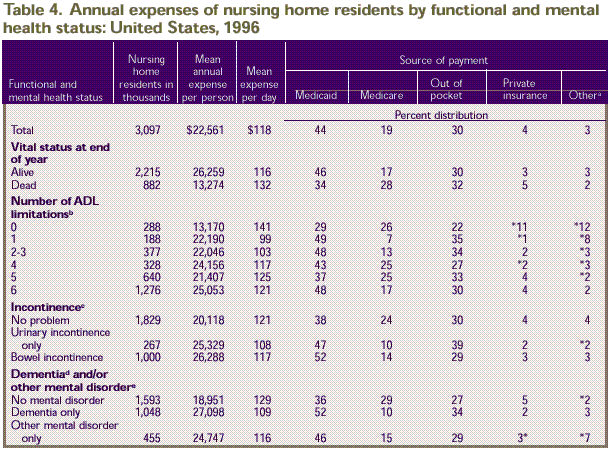

Functional and Mental Health Status

Residents who died during the year had

lower annual nursing home expenses ($13,274) and higher daily

expenses ($132) than residents who were alive at the end of

the year ($26,259 and $116, respectively), as shown in Table

4. Those who died during the year also relied less on

Medicaid (34 percent) and more on Medicare (28 percent) when

compared to those alive at the end of the year (46 and 17

percent, respectively).

Mean annual expenses were lowest ($13,170)

for residents with no limitations in activities of daily living

(ADLs), while their daily expense ($141) was high, reflecting

the fact that these individuals tended to have short stays

(93 days on average in 1996; data not shown) and may have

required a greater concentration of nursing home services.

For residents having one to six ADL limitations, the trend

was for a general increase in average daily expenses, ranging

from $99 for people with one ADL limitation to $125 for those

with five ADL limitations (Table

4).

There was no

difference between the three different categories of incontinence

with respect to daily

expenses ($108–$121). However, residents having urinary

incontinence only or bowel incontinence (with or without urinary

incontinence) had higher annual expenses than those with no

incontinence. This reflects the tendency for incontinent residents

to remain in the nursing home for longer periods of time.

In 1996, average length of stay was 234 days for those with

urinary incontinence only and 225 days for those with bowel

incontinence, compared to 166 days for those without incontinence

(data not shown).

Annual expenses were less for nursing

home residents without mental disorders ($18,951 per person)

than for residents with dementia but no other mental disorder

($27,098). However, those without mental disorders had a higher

daily expense than those with dementia alone, $129 vs. $109.

Residents with no mental disorder had only 36 percent of their

annual expenses paid for by Medicaid, a smaller portion than

for residents with some type of mental disorder. However,

residents with no mental disorders had a greater portion of

annual expenses paid for by Medicare (29 percent) than any

other group.

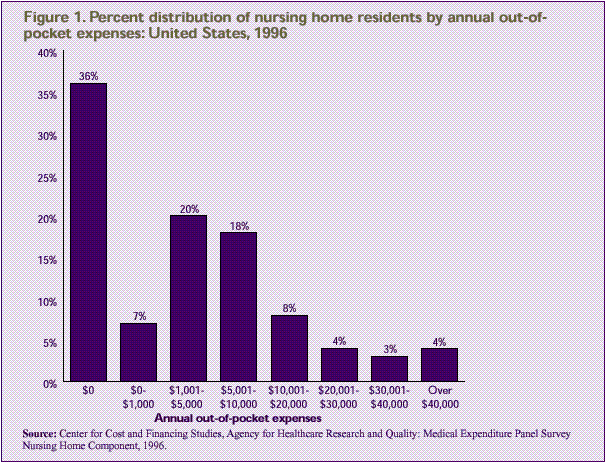

Figure 1 shows

the distribution of nursing home residents by their out-of-pocket

expenses. Forty-three percent of all users spent $1,000 or

less out of pocket, including 36 percent who incurred no out-of-pocket

expenses; 20 percent spent between $1,001 and $5,000, and

18 percent spent between $5,001 and $10,000. Twelve percent

spent between $10,001 and $30,000, and 7 percent exceeded

$30,000.

^top

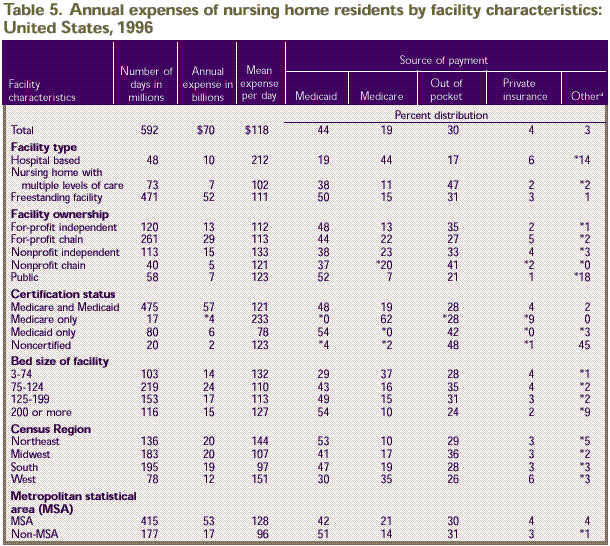

Facility Characteristics

Estimates of average daily expenses indicate

variations in nursing home rates by type of nursing home (Table

5). Individuals in hospital-based nursing homes had a

higher daily expense ($212) than those in freestanding nursing

homes ($111) or nursing homes with multiple levels of care

($102). In addition, residents in hospital-based facilities

were more likely than residents in other types of nursing

homes to rely on Medicare (44 percent) and other (14 percent)

sources of payment and less likely to have their expenses

paid by Medicaid (19 percent) or out of pocket (17 percent).

With respect to nursing home ownership, total annual expenses

were highest in for-profit chain-affiliated nursing homes

($29 billion).

Total annual and average daily expenses

also varied by nursing home certification status. As would

be expected, residents in nursing homes certified by Medicaid

had the largest proportion of their annual expenses paid for

by Medicaid, whether solely Medicaid certified (54 percent)

or dually certified for Medicaid and Medicare (48 percent).

Residents of Medicare-only certified nursing homes had the

highest daily expense ($233), but such payments represented

only a small proportion of the Nation's total annual nursing

home expenditures. For residents in noncertified nursing homes,

the major payers were out of pocket and other source-of-payment

categories. The other source-of-payment category consisted

largely of Department of Veterans Affairs and health maintenance

organization contractual payers.

With regard

to bed size, residents in the smallest nursing homes, 3–74 beds, had a greater

proportion of their annual expenses paid for by Medicare (37

percent) than residents in larger homes. Individuals residing

in the remaining size categories had a greater proportion

of their annual expenses paid for by Medicaid (from 43 to

54 percent) than residents in the smallest homes did. The

greatest proportion of the $70 billion in annual expenses

($24 billion) was represented by residents in homes with 75–124

beds.

^top

Summary

MEPS NHC findings indicate that 1996 annual

nursing home expenses per person with a nursing home stay

averaged $22,561, for an average daily expense of $118. Total

expenses for services in nursing homes amounted to about $70

billion. There was considerable variation in the expenses

and sources of payment for different types of nursing home

residents in different types of facilities.

Thirty-five percent of the 3,097,000 nursing

home residents in 1996 remained in an institution for the

entire year, paying an average of $12,001 per person out of

pocket and incurring total expenses of $36,368 per year. Fifteen

percent of residents were admitted and died in 1996. Their

daily expense was $103 greater than the expense for those

who remained in the nursing home the entire year, but their

total expenses averaged only $9,457 for the year.

Average annual expenses were highest for

women age 90 and over, Medicaid enrollees, residents with

dementia and/or other mental disorders, residents with bowel

incontinence (with or without urinary incontinence), and those

who remained in the nursing home for the entire year. Annual

expenditures were lowest for residents who were discharged

from the nursing home during the year ($8,569).

Average daily expenses were in excess

of $200 for admissions who died during 1996, admissions who

were discharged during the year, and people residing in hospital-based

homes or homes certified for Medicare only. Average expenses

per day were less than $100 for residents with one ADL limitation,

those in facilities certified only for Medicaid, and those

in nursing homes located in the South and in nonmetropolitan

areas.

Medicaid payments for nursing home care

exceeded public payments from any other source, amounting

to 44 percent of the national total and $18,584 (derived from Table

3) per Medicaid enrollee who used a nursing home in 1996.

Medicaid enrollees represented 53 percent of all 1996 nursing

home residents. Medicaid figured most importantly as a payment

source for nursing home residents under age 65, for blacks,

for those who remained in the nursing home the entire year,

and for those with family income less than the poverty level.

While the Medicaid share of nursing home

expenses was substantial, 30 percent of nursing home expenditures

were covered by out-of-pocket payments. Private insurance

contributions to nursing home care amounted to 4 percent of

the total and were concentrated on residents admitted and

discharged from the nursing home during the year (for whom

they constituted 12 percent of total payments) and those with

no ADL limitations (11 percent of total expenses). Nineteen

percent of all nursing home users spent more than $10,000

out of pocket in 1996, and 7 percent spent more than $30,000.

^top

References

Bethel J, Broene

P, Sommers JP. Sample design of the 1996 Medical Expenditure

Panel Survey Nursing

Home Component. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research; 1998. MEPS Methodology Report No. 4. AHCPR Pub.

No. 98–0042.

Dunkle R, Kart C. Long-term care. In:

Ferraro K, editor. Gerontology: perspectives and issues. New

York: Springer Publishing Company; 1990.

Kemper P, Spillman

B, Murtaugh C. A lifetime perspective on proposals for financing

nursing home care.

Inquiry 28:333–344, 1991.

Levit K, Lazenby

H, Braden B, et al. National Health Expenditures, 1996.

Health Care Financing Review 19(1):161–200,

1997.

Potter DEB.

Design and methods of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel

Survey Nursing Home Component.

Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;

1998. MEPS Methodology Report No. 3. AHCPR Pub. No. 98–0041.

Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS. SUDAAN

user's manual: software for the statistical analysis of correlated

data. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute;

1995.

Spence D, Wiener

J. Nursing home length of stay patterns: results from the

1985 National Nursing Home

Survey. The Gerontologist 30(1):16–20, 1990.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Statistical

abstract of the United States: 1996 (116th edition). Washington;

1996.

Wayne S, Rhyen

R, Thompson R, et al. Sampling issues in nursing home research.

Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society 39:308–311, 1991.

^top

Tables

a Vital status

by end of year.

b Other payers include Department of Veterans

Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and other sources

of payment.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

b Includes other racial/ethnic groups not shown

separately.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Note: 0 indicates greater than

zero but less than 0.5.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

b Receiving personal assistance with one or more

of these activities of daily living (ADLs): dressing, bathing,

eating, transferring from a bed or chair, mobility, and

toileting.

c Has difficulty controlling bladder or bowel

several times or more per week. Persons with both types

of incontinence are included in the group with bowel incontinence.

d Includes Alzheimer's and other dementias.

e Includes at least one of the following: anxiety

disorder, depression, manic depression, schizophrenia.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Note: 0 indicates greater than

zero but less than 0.5.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

^top

Figure

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing

Home Component, 1996.

There were substantial

regional differences in expenses. Of all the regions, the West

had the lowest total annual expenses ($12 billion), the lowest

share paid by Medicaid (30 percent), and the highest share

paid by Medicare (35 percent). Annual expenses were comparable

for individuals in the remaining regions, but daily expenses

ranged from a low of $97 in the South to a high of $151 in

the West.

Residents in metropolitan

areas had a higher average daily expense than those in less urbanized

areas ($128 vs. $96), a greater proportion of annual expenses

paid by Medicare (21 percent vs. 14 percent), and a lower proportion

paid by Medicaid (42 percent vs. 51 percent).

^top

Technical Appendix

Data Sources and Methods

of Estimation

The data in this report were obtained

from a nationally representative sample of nursing homes from

the Nursing Home Component (NHC) of the 1996 Medical Expenditure

Panel Survey (MEPS). The sampling frame was derived from the

updated 1991 National Health Provider Inventory. The NHC was

primarily designed to provide unbiased national and regional

estimates for the population in nursing homes, as well as

estimates of these facilities and a range of their characteristics.

The sample was selected using a two-stage

stratified probability design, with facility selection in

the first stage. The second stage of selection consisted of

a sample of residents as of January 1, 1996, and a rolling

sample of persons admitted during the year (Bethel, Broene,

and Sommers, 1998). Estimates in this report are based on

815 eligible responding facilities and 5,899 sample persons.

The MEPS NHC data analyzed here were collected

in person during three rounds of data collection. A computer-assisted

personal interview (CAPI) system was used for data collection.

The entire three-round data collection effort took place over

a 1 1/2 year period, with the reference period being January

1, 1996, to December 31, 1996 (Potter, 1998).

Facility data were obtained from a facility

questionnaire during Round 1 of data collection. Respondents

were facility administrators or designated staff. The facility

questionnaire collected data on facility structure and characteristics

(Potter, 1998).

The facility and community background

sections were used to collect demographic information from

records within the sampled nursing home, as well as from respondents

in the nursing home or community. The facility background

section was administered just once per person, during the

round in which the person was sampled, while the community

background section was administered in either Round 2 or 3

(Potter, 1998).

Most of the health status items collected

in the nursing home were based on the Resident Assessment

Form of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), known

as the minimum data set (MDS). The CAPI application collected

the MDS information in a question format, with question wording,

response categories, and definitions of concepts derived directly

from the MDS. There are multiple versions of the MDS. MEPS

health status questions were based on wording in Version 2

of the MDS. Health status items not based on the MDS were

labeled as such so that interviewers could cue the respondent

to check medical records to obtain the information (Potter,

1998).

The expenditures section of the person-level

facility questionnaire collected data on the costs of nursing

home care during 1996. The data collected included information

on the facility's billing practices, such as the length of

the billing period, the number of days billed for each billing

period, and the rate or rates billed for a person's care.

The section also included information, by billing period,

on all payments received by the facility, the sources of payment

for those services, and the amounts paid by each source of

payment. Expenditure data were first collected in eligible

nursing homes during Round 2 and collected again during Round

3. Typical respondents were facility billing office personnel,

who referred to billing and payment records (Potter, 1998).

The MEPS estimate of national expenditures

for services in nursing homes is $70 billion, considerably

less than the $89 billion estimate for 1996 expenditures from

HCFA's National Health Expenditures (NHE). The NHE figure

includes approximately $1.5 billion in nonpatient revenues,

including philanthropic expenditures, and $9 billion in Medicaid

payments to intermediate care facilities for the mentally

retarded (ICF-MR expenditures). These are excluded from the

MEPS estimate of nursing home expenditures. Thus the NHE estimate

most comparable to the MEPS estimate would be about $78.5

billion (includes $9.0 billion for hospital-based nursing

homes from the hospital spending category of NHE), which is

$8.5 billion more than the MEPS estimate (Levit, Lazenby,

Braden, et al., 1997).

Additionally, the following are possible

sources of the observed discrepancy in expenditure estimates.

- NHE estimates are facility-based estimates.

If a facility is defined as providing nursing care, then

all revenue/receipts to that facility are included in expenditure

estimates. There is the possibility that expenditures for

unlicensed nursing home beds (e.g., assisted living beds

in an assisted living unit) contained within or associated

with the nursing home could be included in expenditure estimates.

For MEPS, approximately 10 percent of beds contained within

sampled nursing homes or associated with them as part of

a larger facility were excluded from expenditure estimates

because they were identified as unlicensed nursing home

beds.

- The NHE are more inclusive than MEPS

with respect to how a nursing home is defined. The following

facilities were included in the NHE but not MEPS: establishments

primarily engaged in providing some (but not continuous)

nursing and/or health-related care, such as convalescent

homes for psychiatric patients that have health care; convalescent

homes with health care; domiciliary care with health care;

personal care facilities with health care; personal care

homes with health care; psychiatric patient convalescent

homes; and rest homes with health care. NHE estimates do

not provide expenditure totals for such facilities separately.

- MEPS excludes nursing homes with fewer

than three beds, while NHE has no limitation because of

the number of nursing home beds.

- MEPS estimates

are based on 16,760 facilities, while NHE estimates are

based on 18,600—an additional

1,840 facilities.

There are also differences in expenditure

estimates methodology. The MEPS estimate of nursing home expenditures

is based on information obtained from the billing records

of each facility used by a sampled person. Total expenditures

for each person and the amounts paid out of pocket and by

third parties were obtained from these records. HCFA, in generating

NHE estimates, uses information collected by the Census Bureau

on State-level receipt/revenue for taxable and tax-exempt

private nursing and personal care facilities from the 1992

Census of Service Industries (CSI). Expenditures for 1996

were generated from the Census Bureau's estimated annual growth

in nursing and personal care facilities taxable and tax-exempt

receipts/revenues from the Service Annual Survey. An estimate

of expenditures for State and local government facilities

is added to the estimated expenditures for private facilities.

Expenditures for State and local government facilities were

estimated from Bureau of Labor Statistics wage data for State

and local government nursing homes. Government nursing home

wages were inflated to revenues based on wage-to-revenue ratios

for private nursing homes that were developed from data collected

by the National Center for Health Statistics in the 1977 National

Nursing Home Survey.

Facility

Eligibility

Only nursing homes were eligible for inclusion

in the MEPS NHC. To be included as a nursing home, a facility

must have at least three beds and meet one of the following

criteria:

- The facility or a distinct portion of

the facility must be certified as a Medicare skilled nursing

facility (SNF).

- The facility or a distinct portion of

the facility must be certified as a Medicaid nursing facility

(NF).

- The facility or a distinct portion of

the facility must be licensed as a nursing home by the State

health department or by some other State or Federal agency

and provide onsite supervision by a registered nurse or

licensed practical nurse 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (Bethel,

Broene, and Sommers, 1998).

By this definition, all SNF- or NF-certified

units of licensed hospitals are eligible for the sample, as

are all Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) long-term care

nursing units. In such cases, and in the case of retirement

communities with nursing facilities, only the long-term care

nursing unit(s) of the facility were eligible for inclusion

in the sample. If a facility also contained a long-term care

unit that provided assistance only with activities of daily

living (e.g., a personal care unit) or provided nursing care

at a level below that required to be classified as a nursing

facility, that unit was excluded from the sample (Potter,

1998).

Resident Sample

To allow a chance of selection for all

persons in this universe, two samples of persons were selected

within each cooperating sampled facility: (1) a cross-sectional

sample of persons who were residents on January 1, 1996 (current

residents) and (2) a sample of persons admitted to the nursing

home at any time during 1996 who had no prior admissions to

an eligible nursing home during 1996 (first admissions). For

details on sampling, refer to Bethel, Broene, and Sommers

(1998).

During Round 1 the interviewer in each

sampled facility compiled a list of current residents as of

January 1, 1996. Within each facility, a systematic random

sample of four current residents was drawn using the CAPI

system. For Rounds 2 and 3, the interviewer compiled a list

of first admissions. A systematic random sample of two first

admissions was drawn for each round and facility.

For a sampled

resident to be considered a respondent, the following questionnaires

had to have been

completed for him or her—the facility residence history

questionnaire in the sampled facility in the round in which

the person was first sampled, as well as at least three of

the following questionnaires: health status, expenditures,

prescribed medicines, and use of medical provider services.

Mean Expense Per Day

and Annual Estimates

Expenditures for nursing home services,

reported in Tables 1–5,

refer to the facility charge for both basic (room and board)

and ancillary (special supplies and services) services. These

charges are limited by the amounts allowed by third-party

payers such as Medicaid, Medicare, and private health insurers.

Missing daily basic expenditures were

imputed for all billing periods in a facility by means of

a weighted sequential hot-deck procedure. This procedure,

which was employed for less than 5 percent of all billing

periods in 1996, imputed data from individuals with expenditure

information to individuals with missing information but similar

characteristics. Groups of similar individuals were formed

according to facility location and type, sources of payment,

Medicaid and Medicare status, family income, and number of

limitations in activities of daily living. Daily expenditures

and sources of payment for persons missing data for some but

not all billing periods in a facility were assigned values

based on the available data for that person. Facilities without

charges (Department of Veterans Affairs nursing homes) were

assigned a facility-level charge based on information provided

by the VA. The VA provided facility-level nursing home rates

for all VA nursing homes within the United States. These rates

were then matched with the small number of VA nursing homes

that were sampled.

Definitions

of Variables

Age

The age of the sample person as of January

1, 1996, was calculated from the date of birth (1996 minus

year of birth) supplied by the respondent. If the date of

birth was unknown, the respondent was asked to provide the

age of the sample person. If the year of birth and age were

both missing (three sample persons), the age of the sample

person was imputed using a mean value imputation, cross-classified

by sex and institutional status.

Marital Status

A constructed

and imputed version of marital status at baseline was used

for estimates. Baseline was measured

at January 1, 1996, for current residents, and at the date

of admission for persons sampled as an admission. Marital

status was collapsed to married and not married (includes

two sample persons less than 15 years of age). The marital

status of sample persons with a value of "don't know" for

marital status (less than 1 percent) was imputed to the modal

value (not married).

Racial/Ethnic Background

Respondents

were asked if the race of each resident was best described

as American Indian, Alaska

Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, black, white, or other.

Race was unknown for eight sample persons; their race was

imputed to the modal value (white). During variable construction

and editing, the "other specified" text fields associated

with an "other race" response were reviewed and

recoded into existing categories of racial/ethnic background

as appropriate. Ethnicity was unknown for less than 1 percent

of the sample (39 sample persons). Missing values for these

cases were imputed to a modal value (non-Hispanic). Estimates

of racial/ethnic background were collapsed into three categories:

white, black, and Hispanic. Other racial/ethnic groups are

included in the white category rather than presented separately

because of small sample size.

Income and Home Ownership

Information on income was collected in

the income and assets section of the community questionnaire.

Income was constructed based on edited versions of the sample

person's gross income and spouse's gross income (if the sample

person was married). All missing values for gross household

income were imputed. The imputation model for gross household

income was run on all households with nonzero income levels.

A natural logarithmic transformation of gross household income

was used to reduce the influence of outliers. Hard boundary

categories were used based on responses to a series of unfolding

questions on income as a percent of the poverty level (based

on marital status and age of the sample person) and Medicaid

eligibility status. The soft boundaries used were marital

status (married vs. not married), education (high school graduate

vs. not), Census Region, age (less than 62 vs. 62 and over),

race (white vs. not white), and sex, in that order. Almost

50 percent of the values for gross income were imputed.

Information on home ownership status at

the date of interview was collected in the income and assets

section of the community questionnaire as well. Additional

information on home ownership was collected in the expenditure

questionnaire and the background section of both the facility

and community questionnaires. This additional information

was used to fill in any missing values. The final edited version

of home ownership reflects information from the four different

sources. When home ownership was unknown, a value was imputed

using a weighted sequential hot-deck procedure. Less than

15 percent of the values for home ownership were imputed.

The reference period for questions pertaining

to income and home ownership was determined by the round in

which the questionnaire was administered. This means that

income and home ownership variables contain values representing

two reference periods. For example, income refers to 1995

when the questionnaire was administered in Round 2 and 1996

when the questionnaire was administered in Round 3.

Poverty Status

Poverty level status was constructed from

gross household income using poverty thresholds published

annually by the U.S. Bureau of the Census. Poverty thresholds

varied by family size (one vs. two persons) and age of householder

(sample person 65 and over vs. under age 65). In the few instances

where family size was greater that two, the poverty thresholds

for family size equal to two were used. Since the reference

period for income was determined by the round of interview,

1995 poverty thresholds were used for sample persons with

responses in Round 2 and 1996 values were used for those with

responses in Round 3.

Activities of Daily Living

Respondents

were asked to indicate whether the sample person had limitations

with personal care activities

commonly known as activities of daily living (ADLs). Six activities

were included: dressing, bathing, eating, transferring from

a bed or chair, mobility, and toileting. Less than 1 percent

of all sample persons were comatose and initially had all

ADLs classified as "inapplicable." These cases,

along with all cases for whom it was indicated that the "activity

did not occur" (less than 2 percent of the total), were

reclassified as having limitations with all ADLs. Persons

with missing data (not more than 1 percent of the total sample

for any ADL) were assumed to have no difficulty with activities

and were reclassified as having no limitations.

Incontinence

Data on bladder

and bowel control were collected from the MDS and refer

to continence in the last

14 days. Residents were classified as incontinent if the response

indicated that they were incontinent or frequently incontinent.

Residents reported to be continent, usually continent, or

occasionally incontinent were classified as having no incontinence.

Responses for bladder and bowel control were collapsed into

three categories: no incontinence; urinary incontinence only;

and bowel incontinence, with or without urinary incontinence.

Less than 1 percent of the sample total were comatose and

initially classified as "inapplicable." These cases

were reclassified as incontinent. Persons with missing data

("don't know") were assumed to have no difficulty

with bowel and/or bladder control and were reclassified as

continent.

Mental Conditions

A question regarding the sample person's

diagnoses and conditions was presented in a list format similar

to that used in the MDS assessment form. It included Alzheimer's

disease; anxiety disorder; dementia, other than Alzheimer's;

depression; manic depression; and schizophrenia.

Facility Type

This variable, constructed from data from

the facility questionnaire, defines the facility's organizational

structure as one of three types:

- Hospital-based nursing home. This

indicates that the sampled nursing home was part of a hospital

or was a hospital-based Medicare SNF.

- Nursing home with multiple levels

of care. This category includes continuing care retirement

communities (CCRCs) and retirement centers that have,

in addition to a nursing home or nursing home unit, independent

living and/or personal care units. It also includes nursing

homes that contain personal care units and non-hospital-based

nursing homes with a separate unit in which personal care

assistance is provided.

- Freestanding facilities. This

category refers to nursing homes with only nursing home

beds. It includes a small number of nursing homes (less

than 1 percent) with an intermediate care unit for the mentally

retarded (ICF-MR).

The order of priority for coding facility

type followed the sequence listed above.

Facility Ownership

Respondents reported the ownership type

that best described their facility (or larger part of the

facility, if the sampled nursing home was part of a larger

facility), as follows:

- For profit (i.e., individual, partnership,

or corporation).

- Private nonprofit (e.g., religious group,

nonprofit corporation).

- One of four

types of public ownership—city/county

government, State government, VA, or other Federal agency.

Respondents also reported whether their

facility was part of a chain or group of nursing facilities

operating under common management.

Facility Certification Status

Respondents were asked whether any unit

in their facility or part of the larger facility (if the sampled

nursing home was reported to be part of a larger facility)

was certified by Medicare as an SNF and/or by Medicaid as

an NF. For the purpose of this report, facilities were assigned

to mutually exclusive categories based on their responses.

Facility Size

The size of the sampled nursing home was

determined by the number of nursing beds regularly maintained

for residents. Beds contained within the sampled nursing home

but not licensed for nursing care were excluded. Unlicensed

beds represented less than 2 percent of the beds in the sampled

nursing homes. If the sampled nursing home was part of a larger

facility, only the licensed nursing home beds were included.

Census Region

Sampled nursing

homes or units were classified in one of four regions—Northeast, Midwest, South, and

West—based on their geographic location according to

the MEPS NHC sampling frame. These regions are defined by

the U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Facility Location

A metropolitan statistical area (MSA)

is defined as including (1) at least one city with 50,000

or more inhabitants or (2) a Census Bureau-defined urbanized

area of at least 50,000 inhabitants and a total metropolitan

population of at least 100,000 (75,000 in New England) (U.S.

Bureau of the Census, 1996). MSA data were missing for 14

facilities; an MSA/non-MSA determination was made after a

review of the county's population density according to the

1990 census.

Reliability

and Standard Error Estimates

Since the statistics presented in this

report are based on a sample, they may differ somewhat from

the figures that would have been obtained if a complete census

had been taken. This potential difference between sample results

and a complete count is the sampling error of the estimate.

The chance that an estimate from the sample

would differ from the value for a complete census by less

than one standard error is about 68 out of 100. The chance

that the difference between the sample estimate and a complete

census would be less than twice the standard error is about

95 out of 100.

Tests of statistical significance were

used to determine whether differences between estimates exist

at specified levels of confidence or whether they simply occurred

by chance. Differences were tested using Z-scores having asymptotic

normal properties, based on the rounded figures at the 0.05

level of significance.

Estimates with a relative standard error

greater than 30 percent are marked with a footnote. Such estimates

cannot be assumed to be reliable.

Rounding

Estimates of percentages presented in

the tables have been rounded to the nearest percent. The rounded

estimates, including those underlying the standard errors,

will not always add to 100 percent or the full total. To avoid

conveying a false sense of precision, estimates of the number

of nursing home users have been rounded to the nearest thousand,

and estimates pertaining to expenditures have been rounded

to the nearest dollar.

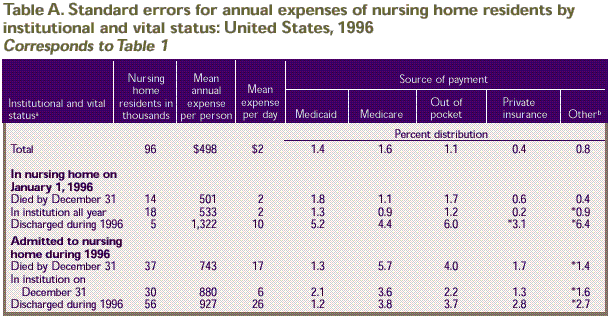

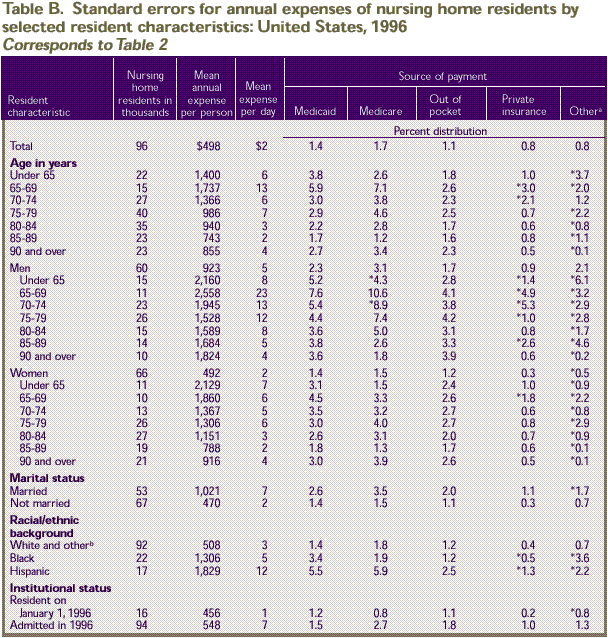

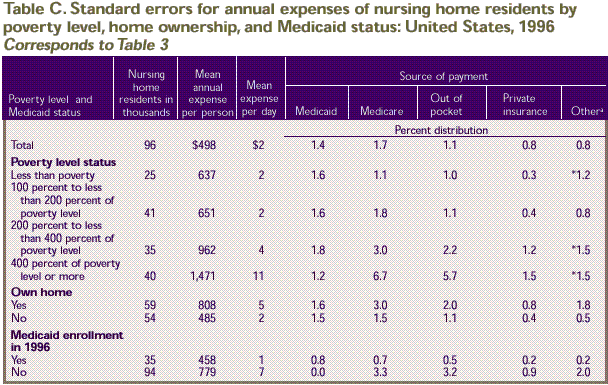

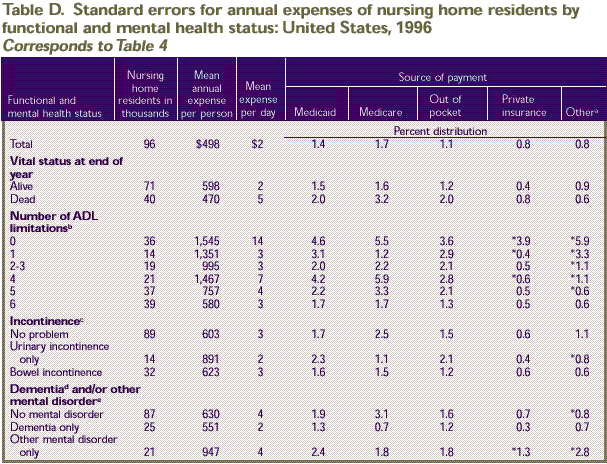

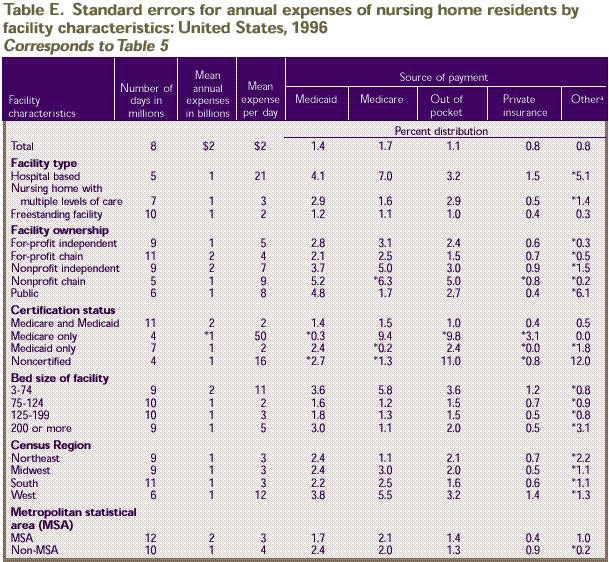

Standard Errors

The standard errors in this report are

based on estimates of standard errors derived using the Taylor

series linearization method to account for the complex survey

design. The standard error estimates were computed using SUDAAN

(Shah, Barnwell, and Bieler, 1995). The direct estimates of

the standard errors for the estimates in Tables

1–5 are provided in Tables

A–E, respectively.

For example, the estimate of $22,561 for

the mean annual expenditure per person (Table

1) has an estimated standard error of $498 (Table

A). The estimate that 67 percent of expenditures for persons

with an income of less than poverty were paid for by Medicaid (Table

3) has an estimated standard error of 1.6 percent (Table

C).

a Vital status by end of year.

b Other payers include Department of Veterans

Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and other sources

of payment.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

b Includes other racial/ethnic groups not shown

separately.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other payers include Department

of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance organizations, and

other sources of payment.

b Receiving personal assistance with one or more

of these activities of daily living (ADLs): dressing, bathing,

eating, transferring from a bed or chair, mobility, and

toileting.

c Has difficulty controlling bladder or bowel

several times or more per week. Persons with both types

of incontinence are included in the group with bowel incontinence.

d Includes Alzheimer's and other dementias.

e Includes at least one of the following: anxiety

disorder, depression, manic depression, schizophrenia.

* Relative standard error is equal to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Financing, Access,

and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality:

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

a Other

payers include Department of Veterans Affairs, health maintenance

organizations, and

other sources of payment. * Relative standard error is equal

to or greater than 30 percent.

Source: Center for Costs and Financing

Studies, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Medical

Expenditure Panel Survey Nursing Home Component.

Note: 1The

MEPS estimate of national expenditures in nursing homes differs

from the estimate in the National Health Expenditures of

the

Health Care Financing Administration. See the technical

appendix for details.

^top

Suggested

Citation:

Rhoades, J. and Sommers, J. Research Findings

#13: Expenses and Sources of Payment for Nursing Home Residents,

1996.

December 2000. Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville,

MD.

http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/rf13/rf13.shtml |

|