Research

Findings #9: Changes in the Medicaid Community Population: 1987-96

Jessica S. Banthin, Ph.D., and Joel W. Cohen,

Ph.D., Agency for Health Care Policy and Research

Abstract

This report uses data from MEPS (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey) and NMES (National Medical Expenditure Survey) to compare the composition of the noninstitutionalized Medicaid population in 1996 and 1987. The Medicaid community population grew significantly over this time period, at the same time as a number of expansions in eligibility rules extended Medicaid coverage to people not receiving cash assistance. In both years, children, the elderly, minorities, and the nonworking population were more likely than others to be enrolled in Medicaid, as were the sick and disabled. Children made up nearly half of the Medicaid community population in both years. The composition of the Medicaid community population shifted slightly but significantly over the decade. There were relatively higher proportions of whites and men and relatively lower proportions of women and blacks in 1996 than in 1987. The proportion of the total Medicaid community population made up of non-elderly adults fell during this time period, but a much greater proportion of these non-elderly Medicaid adults were employed in 1996 than in 1987. Also, in 1996 many more of the parents of Medicaid-enrolled children worked. These shifts have significant implications for the administration of Medicaid.

^top

Introduction

Medicaid is the main public program for providing

health insurance coverage to poor and low-income Americans. Traditionally,

the population served by Medicaid has also tended to be in poorer

health than higher income segments of the population (Cohen, Cornelius,

Hahn, et al., 1994). Over the past decade, however, there have

been many changes in the Medicaid community population, which is

defined here as Medicaid enrollees among the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized

population.1 The size of

the community population served by Medicaid grew significantly

in the past decade, from 7.3 percent of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized

population in the first part of 1987 to 11.9 percent in the first

part of 1996. In the first part of 1987, Medicaid covered an estimated

17.5 million people, compared with 31.4 million in the first part

of 1996. This growth occurred at the same time that numerous Federal

and State legislative initiatives have expanded Medicaid eligibility

beyond the traditional populations served—people receiving

cash assistance.

This report describes the demographic, health status,

and employment characteristics of the Medicaid community population

in the first part of 1996. It also examines how the Medicaid population

changed in terms of demographic and employment measures between the

first part of 1987 and the first part of 1996. Data for this report

were derived from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)

Household Component (HC) and the 1987 National Medical Expenditure

Survey (NMES) Household Survey.

With the increase in the size of the Medicaid

program have also come changes in the composition of the enrolled

Medicaid community population. These changes can have important

implications for the mix of services paid for by Medicaid, the

move to managed care plans, and the success of outreach efforts.

Changes in the format of questions on general perceived health

status and limitations in work, school, and housework between the

1987 NMES and the 1996 MEPS preclude the direct comparison of changes

in health status. Therefore, this report cannot provide direct

comparisons of health status measures between early 1987 and early

1996. However, the data show that in the first part of 1996 the

Medicaid program continued to serve a population that was in poorer

health than the overall U.S. community population.

Many factors are responsible for shifts in

the size and composition of the Medicaid community population over

time. These factors can be broadly grouped into three categories:

programmatic, demographic, and general economic trends. The most

immediate and significant expansions in Medicaid coverage rates

are often related to changes in program eligibility criteria or

administrative practices. Other factors, however, such as larger

relative increases in the number of young children in the United

States or a drop in the unemployment rate, also can affect Medicaid

coverage rates by changing the size of the pool of potentially

eligible Medicaid enrollees. It is not the intention of this report

to break down the causes of increases in the Medicaid population.

However, a brief summary of the main legislative changes is useful

for understanding the fluctuations in the Medicaid community population

between 1987 and 1996.

^top

Expansions in Medicaid

Eligibility Criteria

Until the mid-1980s, Medicaid coverage for

the community population was largely limited to poor women, children,

and disabled people receiving cash assistance (particularly AFDC

and SSI).2 Some States also

provided Medicaid coverage to other people through programs for

the medically needy. In the past decade, however, numerous legislative

initiatives at both the Federal and State levels have expanded

Medicaid coverage to certain low-income groups beyond those who

are receiving cash assistance. Beginning with the Deficit Reduction

Act of 1984 and continuing through the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation

Act (OBRA) of 1990, most of the Federal initiatives were specifically

targeted to low-income children and pregnant women. It is estimated

that the Federal and State expansions doubled the number of children

eligible for Medicaid on a national basis (Selden, Banthin, and

Cohen, 1998).

Current law as of 1996 established Medicaid

eligibility for infants, children up to age 6, and pregnant women

whose family income was not over 133 percent of the poverty level,

regardless of whether they received AFDC. Children born after September

30, 1983, whose family income was up to 100 percent of the poverty

level were also eligible for Medicaid. As of the first part of

1996, this rule covered children age 12 and under. This phased-in

expansion, referred to as the Waxman expansion, will include all

children under age 19 with incomes up to 100 percent of the poverty

level by 2002. Federal law also permits States the option of allowing

Medicaid eligibility up to 185 percent of the poverty level for

any of these groups of women and children, and some States have

done so.

The Family Support Act of 1988 expanded coverage

for whole families, including working-age men who were fathers

of AFDC- or Medicaid-eligible children. The Act mandated all States

to include the AFDC Unemployed Parents provision, which grants

cash assistance and Medicaid coverage to intact families that meet

the income requirement. It also extended Medicaid coverage for

12 months to families who lose AFDC assistance because of increased

earnings.

In addition to Federal initiatives, several States

have used Section 1115 "Research and Demonstration" waivers

to expand access to publicly sponsored health insurance to a more

broadly defined low-income and uninsured population. Programs such

as Tenncare are open to low-income families and persons beyond

the traditional Medicaid-eligible groups, including, for example,

nondisabled childless adults. Many of these programs have varying

levels of cost-sharing and premium payments for eligible families

depending on poverty status.

Another area of expansion affects certain low-income

elderly and disabled people. Sections of the Medicare Catastrophic

Coverage Act of 1988 presently in effect expanded Medicaid coverage

to the low-income elderly and the low-income disabled. The Act

requires that Medicaid pay for the Medicare cost-sharing requirements

and premium payments for certain low-income qualified Medicare

beneficiaries (the so-called dual eligibles).

Finally, growth in the SSI program also has

affected Medicaid enrollment. The definition of qualifying disabilities

was broadened for children because of legislative mandates and

through court decisions, such as the Zebley decision, that expanded

the definition of disabilities (Sullivan v. Zebley, 1990, 493 U.S.

521). SSI coverage also has grown to include people with AIDS and

people with severe substance abuse problems.

^top

Changes in Medicaid Enrollment

Rates

Age and Sex

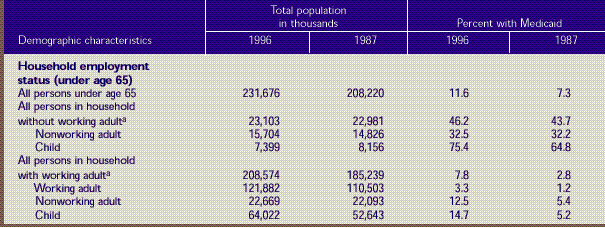

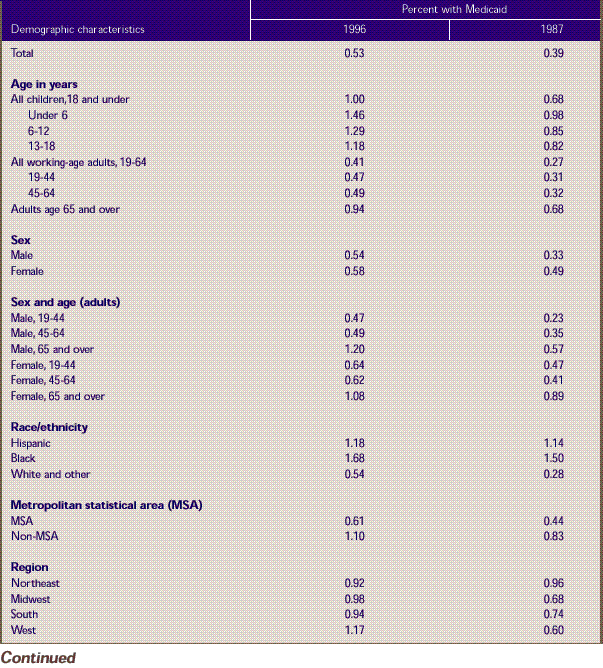

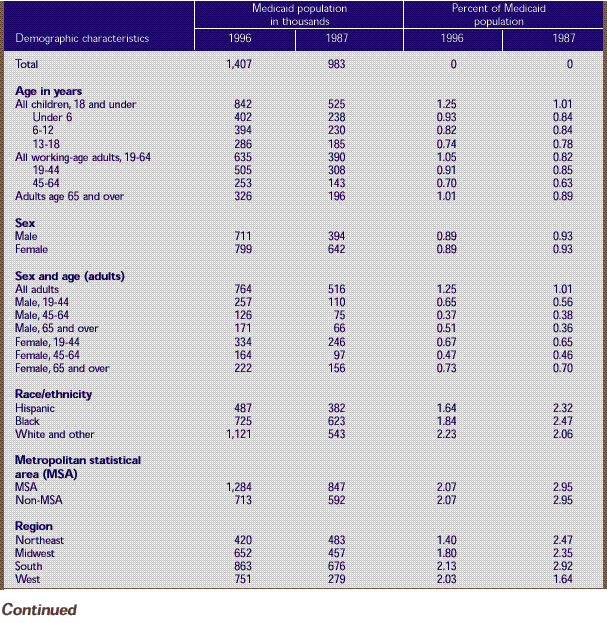

Table 1 compares

Medicaid enrollment rates as a percentage of the total U.S. community

population in the first part of 1996 and the first part of 1987.

The first section of Table 1 shows

the distribution of Medicaid enrollees by age category. The proportion

of all children covered by Medicaid increased substantially, rising

from 12.8 percent of all children under age 19 in the first part

of 1987 to 20.5 percent of all children in the first part of 1996.

While all age groups showed an increase, the most dramatic increase

was among those targeted by Medicaid expansions—children under

age 6—whose enrollment rose from 16.2 percent in 1987 to 25.8

percent in 1996. Medicaid enrollment for children ages 6-12 rose

from 13.2 percent in 1987 to 21.0 percent in 1996. Teens ages 13-18

had lower Medicaid enrollment than younger children, but their

rates rose too—from 9.4 percent in 1987 to 14.2 percent in

1996.

There was a large increase in Medicaid coverage

of people age 65 and over, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibles. Medicaid

coverage rates for the community population in this age group increased

from 7.6 percent in 1987 to 14.1 percent in 1996. The largest absolute

increases between 1987 and 1996 were among children (7.7 percentage

points) and among the elderly (6.5 percentage points). Relatively

small increases were seen among working-age adults (2.6 percentage

points).

The next section of Table

1 shows that the absolute increases in Medicaid coverage

rates for all ages combined were similar for females and males,

although females were covered by Medicaid at a higher rate than

males. In 1996, 13.2 percent of females were enrolled in Medicaid,

an increase of 4.3 percentage points from 1987; 10.6 percent

of males were enrolled in 1996, an increase of 4.9 percentage

points from 1987.

In the next section of Table

1, coverage rates for adults are shown by age and sex. Even

though pregnant women were targeted by Medicaid expansions, enrollment

rates for women ages 19-44 increased by only 29 percent between

1987 and 1996, rising from 8.0 to 10.3 percent. Coverage rates

for men of the same age more than doubled between 1987 and 1996,

increasing from 2.5 to 5.6 percent. As mentioned earlier, the

Family Support Act of 1988 expanded Medicaid eligibility for

low-income working-age fathers of young children.

The highest levels of coverage of adults were

among the elderly. In 1996, about 15.9 percent of elderly women

were enrolled in Medicaid, up from 9.6 percent in 1987; 11.7 percent

of elderly men were enrolled in 1996, up from 4.7 percent in 1987.

Race/Ethnicity

Differences in Medicaid enrollment rates by

racial and ethnic group are shown in the next section of Table

1. The first two columns of data show the markedly different

rates of growth in the U.S. community population by racial and

ethnic group. The number of Hispanics in the United States increased

by 51 percent between 1987 and 1996, blacks increased by 16 percent,

and whites and others (including Asians, Pacific Islanders, American

Indians, and Alaska Natives) increased by approximately 6 percent.

At the same time, Medicaid enrollment rates increased from 16.9

percent to 21.0 percent among Hispanics and from 4.1 percent to

8.4 percent among the group of whites and others, with no significant

change among blacks.

Location

The next two sections of the table look at

urban and regional differences. While there was a decrease in the

number of people in the U.S. community population living outside

metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) from 1987 to 1996, the rate

of Medicaid enrollment grew faster in non-MSAs (rising from 8.1

percent to 13.9 percent) than in MSAs (increasing from 7.1 percent

to 11.4 percent). The West Region of the country experienced not

only an increase in overall population but also a large increase

in Medicaid coverage rates. Medicaid enrollment in the West grew

8.2 percentage points, from 5.9 percent of the population in 1987

to 14.1 percent in 1996.

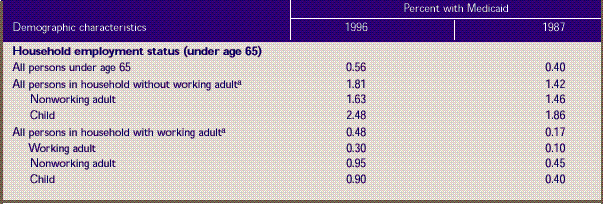

Employment Status

In examining how Medicaid enrollment has changed

with respect to employment status, the sample is subset to people

under age 65 in the last section of Table

1. The total number of people who lived in households without

an employed adult (ages 18-64) stayed relatively constant between

1987 and 1996 in spite of the increase in the overall U.S. population,

while the number of children living in these households fell slightly

from 8.2 million to 7.4 million. Yet, three-quarters (75.4 percent)

of all children who lived in a household without an employed adult

were enrolled in Medicaid in 1996, up from 64.8 percent in 1987.

The percent of people enrolled in Medicaid

who were living in households with an employed adult increased

overall from 2.8 percent in 1987 to 7.8 percent in 1996. The largest

increase was among children, whose rate of enrollment rose from

5.2 percent in 1987 to 14.7 percent in 1996. The change in eligibility

criteria that grants Medicaid coverage to some children and pregnant

women based on poverty status rather than AFDC eligibility may

explain this rise. In spite of holding jobs, some families still

qualify for Medicaid coverage of some or all members of the family.

^top

Demographic Changes

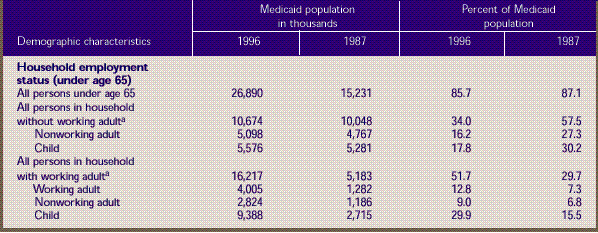

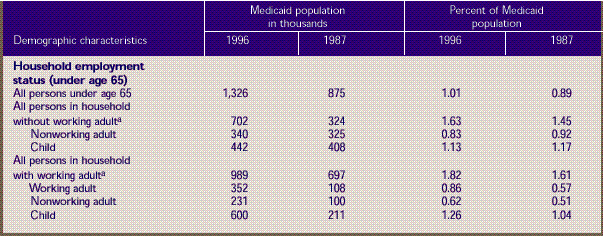

Table 2 shows

how the composition of the Medicaid community population changed

between early 1987 and early 1996. The distribution of enrollees

as a percentage of the total Medicaid community population is shown

by selected demographic characteristics. The overall Medicaid population

grew from 17.5 million in the first part of 1987 to 31.4 million

in the first part of 1996. In addition, the composition of the

Medicaid population shifted in some significant ways, reflecting

increases in the rates of enrollment by different subgroups as

well as changes in the overall U.S. population.

The first section of Table

2 shows that children still made up slightly less than half

(48.9 percent) of the Medicaid community population in 1996.

This percentage did not change significantly despite relatively

larger increases in children's enrollment rates as well as larger

increases in overall population numbers compared with other age

groups. The percentage of adults ages 19-44 fell by 3.2 percentage

points to 26.7 percent of the total community Medicaid population

in 1996. The percentage of elderly adults rose from 12.9 percent

in 1987 to 14.3 percent in 1996, but this is not a statistically

significant change.

Medicaid enrollees are also shown by sex and

age-sex categories. Medicaid programs were more likely to cover

men in 1996 than in 1987. The percentage of males in the Medicaid

community population grew to 43.3 percent of the total in 1996,

compared with 37.8 percent in 1987. Although the absolute number

of women ages 19-44 enrolled in Medicaid increased from 4.0 million

in 1987 to about 5.5 million in 1996, this group made up only 17.4

percent of the total Medicaid community population, down from 23.0

percent in 1987. At the same time, men ages 19-44 increased from

6.8 to 9.2 percent of the total. Although small, these changes

in composition can have implications for the mix of services paid

for by the Medicaid program, since working-age men and women have

different health care needs from each other and from the needs

of young children and the elderly.

There also have been significant changes by racial

and ethnic group. Whites and others made up more than half (54.4

percent) of the Medicaid community population in 1996, while blacks

fell to 26.6 percent of the total. This is a significant shift

from 1987, when whites and others composed 44.6 percent and blacks

composed 37.4 percent of the total Medicaid community population.

Hispanics stayed nearly constant, at 19.0 percent of the total

in 1996 and 18.1 percent of the total in 1987.

Changes by urban and geographic region are

shown in the next section of Table 2. There

were no significant shifts in the percentage of the Medicaid community

population living in urban areas. Medicaid enrollees living in

the West made up a greater percentage of the total Medicaid population

in 1996 than in 1987 (26.1 percent versus 15.8 percent).

The last section of Table

2 shows only people under age 65 and compares the changes

in the Medicaid community population by household employment

status. Employed adults (ages 18-64) composed 12.8 percent of

the Medicaid community population in 1996, up from 7.3 percent

in 1987. Children who lived in a household with an employed adult

made up 29.9 percent of the total Medicaid community population

in 1996, compared with just 15.5 percent in 1987. Conversely,

children who lived in households without an employed adult made

up 17.8 percent of the total in 1996, down from 30.2 percent

in 1987.

^top

Changes in Parents' Employment

Status

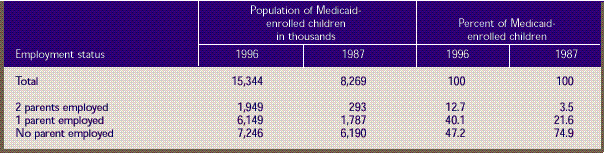

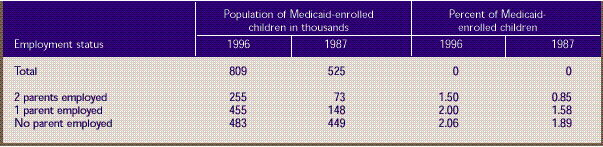

Table 3 looks

at Medicaid-enrolled children specifically in terms of the employment

status of their parents. Children in both one- and two-parent households

are included. The composition of the group of Medicaid-enrolled

children changed dramatically from 1987 to 1996 in terms of their

parents' employment status. Whereas in 1987 three-quarters (74.9

percent) of Medicaid-enrolled children lived in households with

no employed parent, this group fell to less than half (47.2 percent)

of all Medicaid-enrolled children in 1996. The percentage with

one or two employed parents increased to 52.8 percent in 1996,

up from 25.1 percent in 1987.

^top

Health Status, 1996

One of the main objectives of the Medicaid

program has always been to ensure access to health care for people

who need care but cannot pay for it on their own. In addition to

being in greater economic need, the population served by Medicaid

generally has tended to be less healthy than the non-Medicaid population.

There also has been considerable interest in recent years in the

relationship between health status and health insurance. Tables

4-6 examine the relationship between health status and Medicaid

coverage for three separate populations of interest: children,

non-elderly adults, and adults age 65 and over.

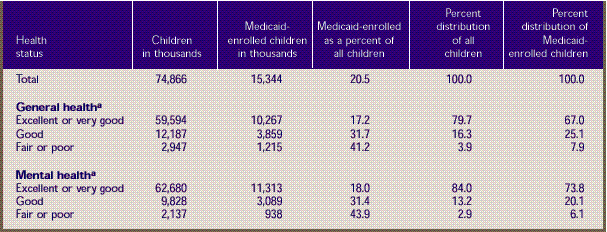

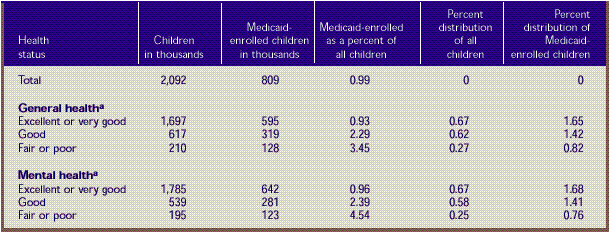

Table 4 presents

data on health status and Medicaid coverage for children age 18

and under. The probability that a child is enrolled in Medicaid

is associated with the state of both the child's general and mental

health. Children in fair or poor health are much more likely than

those in excellent or very good health to be covered by Medicaid.

In 1996, 41.2 percent of children in fair or poor general health

and 43.9 percent of those in fair or poor mental health were enrolled

in Medicaid, in contrast to the enrollment rates for children in

excellent or very good general health (17.2 percent) and excellent

or very good mental health (18.0 percent). Moreover, compared with

the total population of children ages 18 and under, those on Medicaid

were:

- Less likely to be in excellent or very good

general health (79.7 percent of the total population vs. 67.0

percent of children enrolled in Medicaid) or mental health (84.0

percent of the total population vs. 73.8 percent).

- Twice as likely to be in fair or poor general

health (3.9 percent of the total population versus 7.9 percent

for Medicaid) or mental health (2.9 percent of the total population

versus 6.1 percent).

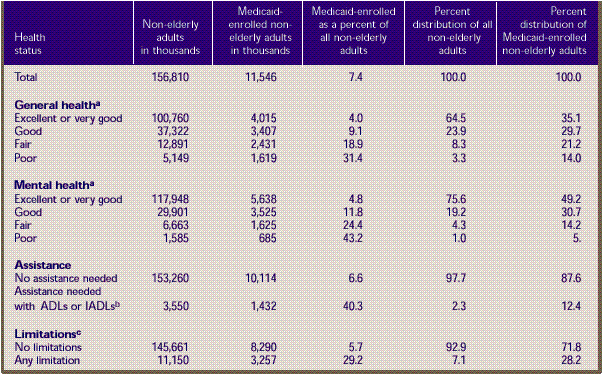

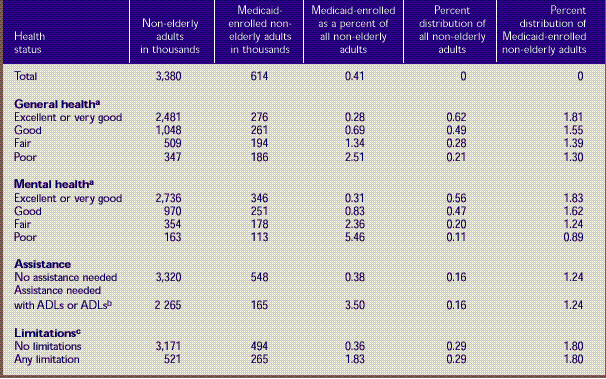

Table

5 presents similar data for the non-elderly adult

population (ages 19-64). As was the case with children,

non-elderly adults in fair or poor health are much

more likely than their healthier counterparts to be

covered by Medicaid. Non-elderly adults who need assistance

with activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental

activities of daily living (IADLs) and those who have

activity limitations are also more likely to be covered

by Medicaid. For each measure, the probability of being

enrolled in Medicaid increases as health status declines.

For example, only 4.0 percent of non-elderly adults

in excellent or very good general health, but nearly

one-third (31.4 percent) of non-elderly adults in poor

general health, were covered by the program in 1996.

Similarly, non-elderly adults who needed ADL or IADL

assistance were approximately six times as likely as

those who did not need such assistance to be enrolled

in Medicaid (40.3 percent compared with 6.6 percent).

Medicaid's orientation toward people

who have health problems can also be seen in the health

status of non-elderly adult program enrollees compared

with the health status of the total U.S. population this

age. For example, people in excellent or very good health

make up nearly two-thirds (64.5 percent) of the total

non-elderly adult population but only about one-third

(35.1 percent) of the Medicaid population this age. Similarly,

while only 7.1 percent of the total non-elderly adult

population had any activity limitations, more the one-quarter

(28.2 percent) of the comparable Medicaid population

had a limitation of some kind. Finally, non-elderly adults

covered by Medicaid were nearly six times as likely as

the total population this age to be in poor mental health

(5.9 percent versus 1.0 percent) or to need ADL or IADL

assistance (12.4 percent versus 2.3 percent).

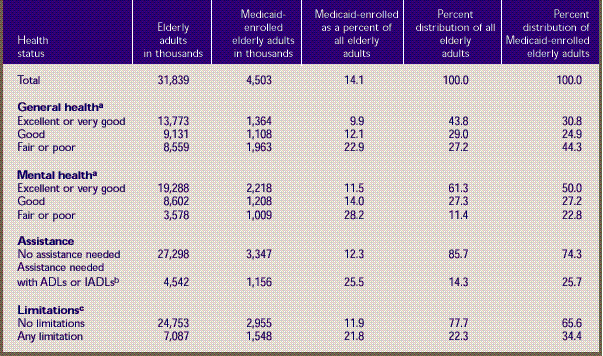

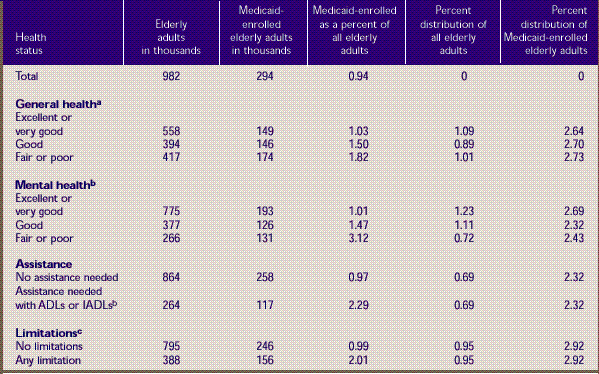

Table 6 presents

health status data for the elderly noninstitutionalized

Medicaid population (age 65 and over). As is true for

both children and non-elderly adults, the probability

of being enrolled in Medicaid increases as the health

status of the elderly declines. For example, elderly

persons whose general health status was excellent or

very good were less than half as likely to be enrolled

in Medicaid as those whose health status was only fair

or poor (9.9 percent versus 22.9 percent). The same was

true for mental health (11.5 percent versus 28.2 percent).

Elderly individuals who did not need ADL or IADL assistance

were less than half as likely to be enrolled in Medicaid

as those who needed such assistance (12.3 percent vs.

25.5 percent). In 1996, elderly Medicaid enrollees were

much more likely than the total elderly population:

- To be in fair or poor general health

(44.3 percent versus 27.2 percent).

- To be in fair or poor mental health

(22.8 percent vs. 11.4 percent).

- To need ADL or IADL assistance (25.7

percent vs. 14.3 percent).

- To have an activity limitation (34.4

percent vs. 22.3 percent).

^top

Conclusions

The Medicaid community population

grew significantly from 1987 to 1996, at the same time

as a number of expansions in eligibility rules extended

Medicaid coverage to people not receiving cash assistance.

The pattern in both years was that children, the elderly,

women, minorities, and the nonworking populations were

more likely than others to be enrolled in Medicaid. Medicaid

also was more likely to serve the sick and disabled.

Data for 1996 show that people in poor general or mental

health and people with limitations or in need of assistance

in daily living were more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid

then healthy nondisabled persons were.

The composition of the Medicaid community

population shifted slightly but significantly from 1987

to 1996. There were relatively higher proportions of

whites and men and relatively lower proportions of women

and blacks in 1996 than in 1987. Children composed nearly

half of Medicaid enrollees in both years. The proportion

of the total Medicaid community population consisting

of non-elderly adults fell, but employed adults constituted

a much greater proportion of non-elderly Medicaid-enrolled

adults in 1996 than in 1987. This was also true for the

parents of Medicaid-enrolled children; many more of the

parents in 1996 than in 1987 were employed. Thus, concurrent

with a number of important expansions in Medicaid eligibility

rules, enrollment patterns and the makeup of the Medicaid

community population changed from 1987 to 1996. These

shifts have significant implications for the administration

of such an important insurance program for low-income

individuals and families.

^top

Tables

Table 1. Demographic

characteristics of the total population and percent

with Medicaid: U.S. community population, first half

of 1996 and first half of 1987

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical Expenditure

Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table 2. Demographic

characteristics of the Medicaid population: U.S.

community population, first half of 1996 and first

half of 1987

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical Expenditure

Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table 3. Employment

status of parents of Medicaid-enrolled children age

18 and under: U. S. community population, first half

of 1996 and first half of 1987

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical Expenditure

Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table 4. Health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled children age

18 and under: U.S. community population, first half

of 1996

- aItem nonresponse was

less than 0.1 percent of all responses. Distributional

estimates on health status were made on the assumption

that nonrespondents followed the distribution of respondents.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

Table 5. Health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled adults ages

19-64: U.S. community population, first half of 1996

- a Item nonresponse was

0.6 percent of all responses. Distributional estimates

on health status were made on the assumption that nonrespondents

followed the distribution of respondents.

- b Activities of daily

living (ADLs) include activities such as bathing and

dressing. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

include activities such as shopping and paying bills.

- c Limitations involve

the ability to work at a job, do housework, or go to

school.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

Table 6. Health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled adults age

65 and over: U.S. community population, first half

of 1996

- a Item

nonresponse was 1.5 percent of all responses. Distributional

estimates on health status were made on the assumption

that nonrespondents followed the distribution of respondents.

- b Activities of daily

living (ADLs) include activities such as bathing and

dressing. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

include activities such as shopping and paying bills.

- c Limitations involve

the ability to work at a job, do housework, or go to

school.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

References

Cohen J. Design and methods of the

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component.

Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;

1997. MEPS Methodology Report No. 1. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0026.

Cohen J, Cornelius L, Hahn B, et

al. Use of services and expenses for the noninstitutionalized

population under Medicaid. Rockville (MD): Agency for

Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. National Medical

Expenditure Survey Research Findings 20. AHRQ Pub. No.

94-0051.

Cohen JW, Monheit AC, Beauregard

KM, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national

health information resource. Inquiry 1996;33:373-89.

Cohen S. Sample design of the 1996

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component.

Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;

1997. MEPS Methodology Report No. 2. AHRQ Pub. No. 97-0027.

Cohen S, DiGaetano R, Waksberg J.

Sample design of the Household Survey. Rockville (MD):

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1991. National

Medical Expenditure Survey Methods 3. AHRQ Pub. No. 91-0037.

Edwards WS, Berlin M. Questionnaires

and data collection methods for the Household Survey

and the Survey of American Indians and Alaskan Natives.

Rockville (MD): National Center for Health Services Research

and Health Care Technology Assessment; 1989. National

Medical Expenditure Survey Methods 2. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS)

89-3450.

Selden TM, Banthin JS, Cohen JW.

Medicaid's problem children: eligible but not enrolled.

Health Affairs 1998;17(3):192-200.

Short P, Monheit A, Beauregard K.

A profile of uninsured Americans. Rockville (MD): National

Center for Health Services Research and Health Care Technology

Assessment; 1989. National Medical Expenditure Survey

Research Findings 1. DHHS Pub. No.( PHS) 89-3443.

Vistnes JP, Monheit AC. Health insurance

status of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population:

1996. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and

Research; 1997. MEPS Research Findings No. 1. AHRQ Pub.

No. 97-0030.

^top

Technical Appendix

The data in this report were obtained

in the first round of interviews for the Household Component

(HC) of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)

and the Household Survey of the 1987 National Medical

Expenditure Survey (NMES). MEPS is cosponsored by the

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) and

the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NMES

was sponsored by AHRQ's predecessor, the National Center

for Health Services Research. Both are nationally representative

surveys of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population

that collect medical expenditure data at both the person

and household levels.

The focus of the MEPS HC and the

NMES Household Survey is to collect detailed data on

demographic characteristics, health conditions, health

status, use of medical care services, charges and payments,

access to care, satisfaction with care, health insurance

coverage, income, and employment. In other components

of MEPS and NMES, data are collected on residents of

licensed or certified nursing homes and on the supply

side of the health insurance market.

Survey Design

1996 MEPS

The sample for the 1996 MEPS HC was

selected from respondents to the 1995 National Health

Interview Survey (NHIS), which was conducted by NCHS.

NHIS provides a nationally representative sample of the

U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population and reflects

an oversampling of Hispanics and blacks.

The MEPS HC collects data through

an overlapping panel design. In this design, data are

collected through a precontact interview that is followed

by a series of five rounds of interviews over 2 1/2 years.

Interviews are conducted with one member of each family,

who reports on the health care experiences of the entire

family. Two calendar years of medical expenditure and

utilization data are collected from each household and

captured using computer-assisted personal interviewing

(CAPI). This series of data collection rounds is launched

again each subsequent year on a new sample of households

to provide overlapping panels of survey data that will

provide continuous and current estimates of health care

expenditures. The reference period for Round 1 of the

MEPS HC was from January 1, 1996, to the date of the

first interview, which occurred during the period from

March through July 1996.

1987 NMES

The 1987 NMES was designed to provide

estimates of insurance coverage, use of services, expenditures,

and sources of payment for the 1-year period from January

1, 1987, through December 31, 1987. The entire Household

Survey was conducted in four interview rounds at approximately

4-month intervals, with a fifth short telephone interview

at the end. Items related to health status, access to

health care, and income were collected in special supplements

that were administered over the course of the calendar

year. The reference period for Round 1 of the Household

Survey was from January 1, 1987, to the date of the first

interview, which took place at some time from February

through April 1987. For more information on the survey

instruments and data collection methods for NMES, see

Edwards and Berlin (1989).

Medicaid Coverage

The household respondent was asked

if—between the first of the year and the time of

the Round 1 interview—anyone in the family was covered

by any of several sources of public and private health

insurance coverage. For this report, Medicaid enrollment

represents coverage at any time during the Round 1 reference

period. Persons identified as having Medicaid coverage

could also have had other sources of public and private

coverage. For more details on health insurance status

measures, see Vistnes and Monheit (1997) for information

on the 1996 MEPS and Short, Monheit, and Beauregard (1989)

for information on the 1987 NMES.

Respondents were asked if they were

covered by Medicaid, medical assistance, or some other

State-specific name for the Medicaid program. In editing

the 1996 data, a small number of cases reporting Aid

to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) or Supplemental

Security Income (SSI) coverage (questions included in

Round 1 for editing purposes) were assigned Medicaid

coverage. To identify Medicaid recipients who might not

have recognized their coverage as Medicaid, respondents

who did not report Medicaid coverage were asked if they

were covered by any other public hospital/physician coverage.

If they said yes, they were identified as Medicaid enrollees.

In editing the 1987 NMES data, the

Medicaid status of approximately 150 persons with missing

data was inferred from family relationships, receipt

of SSI and AFDC, whether Medicaid was reported as a source

of payment for a person's medical expenses, employment

information, and poverty status of the persons living

in the dwelling unit at the time of the screening interview.

The accuracy of Medicaid reporting

in household surveys can be assessed by comparisons with

Medicaid administrative data. The administrative data

are counts of the number of persons who were covered

by Medicaid at any point during the year. Thus, they

can be compared appropriately to full-year estimates

rather than the part-year estimates used in this report.

Full-year estimates from the 1996 MEPS are not available

for this report. However, full-year estimates from the

1987 NMES show that Medicaid estimates for NMES were

only 4.7 percent below administrative enrollment counts.

For further information on the accuracy of Medicaid reporting,

see Selden, Banthin, and Cohen (1998).

Population Characteristics

Information on all population characteristics

used in this report comes from Round 1 of either the

1996 MEPS HC or the 1987 NMES Household Survey.

Race/Ethnicity

Classification by race and ethnicity

is based on information reported for each family member.

Respondents were asked if their race was best described

as American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander,

black, white, or other. In this report, American Indians,

Alaska Natives, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are included

with whites in the category "white and other."

Respondents also were asked if each

family member's main national origin or ancestry was

Puerto Rican; Cuban; Mexican, Mexicano, Mexican American,

or Chicano; other Latin American; or other Spanish. All

persons whose main national origin or ancestry was reported

in one of these Hispanic groups, regardless of racial

background, were classified as Hispanic. Since the Hispanic

grouping can include black Hispanic, white Hispanic,

and other Hispanic, the race categories of black and

white/other do not include Hispanic persons.

Region and Place of Residence

Individuals were identified as residing

in one of four main regions—Northeast, Midwest,

South, and West—in accordance with the U.S. Bureau

of the Census definition. Place of residence, either

inside or outside a metropolitan statistical area (MSA),

was defined according to the U.S. Office of Management

and Budget designation, which applied 1990 standards

using population counts from the 1990 U.S. census. An

MSA is a large population nucleus combined with adjacent

communities that have a high degree of economic and social

integration with the nucleus. Each MSA has one or more

central communities containing the area's main population

concentration. In New England, metropolitan areas consist

of cities and towns rather than whole counties.

Age

The respondent was asked to report

the age of each family member as of the date of the Round

1 interview.

Household Employment Status

A household (family) was defined as

a group of people living together who were related to

one another by blood, marriage (or living together as

married), or adoption or foster care. For this report,

presence of an employed adult was defined as having a

person living in the household at the time of the Round

1 interview who was age 18-64 and had a paying job.

Health Status, 1996

Health status measures used in this

report are from the 1996 MEPS only. In every round of

MEPS, the respondent is asked to rate the health of every

member of the family. The exact wording of the question

is: "In general, compared to other people of (PERSON)'s

age, would you say that (PERSON)'s health is excellent,

very good, good, fair, or poor?" A similar question

is asked about mental health status.

In order to generate the distributional

estimates presented in Tables 4-6, it was assumed that

persons missing data for these questions were distributed

across health states following the distribution of those

with data available.

Assistance with ADLs and IADLs

Questions concerning the need for

assistance in instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs) and in activities of daily living (ADLs) are

asked in every round of MEPS. Limitations in the ability

to perform IADLs are assessed by first asking the respondent

a screening question: "Does anyone in the family

receive help or supervision using the telephone, paying

bills, taking medications, preparing light meals, doing

laundry, or going shopping?" Limitations in ability

to perform ADLs are assessed with the following question: "Does

anyone in the family receive help or supervision with

personal care such as bathing, dressing, or getting around

the house?" Follow-up questions are asked, but they

are not used in this report. For this report, the responses

to the two screening questions are combined into a single

measure of need for any type of IADL or ADL assistance.

Activity Limitations

These include limitations in both

paid work and unpaid housework, as well as limitations

in the ability to attend school. The relevant question

asks, "Is anyone in the family limited in any way

in the ability to work at a job, do housework, or go

to school because of an impairment or a physical or

mental health problem?" (emphasis in the question

as indicated).

Sample Design and Accuracy of Estimates

1996 MEPS

The sample selected for the 1996

MEPS, a subsample of the 1995 NHIS, was designed to produce

national estimates that are representative of the civilian

noninstitutionalized population of the United States.

Round 1 data were obtained for approximately 9,400 households

in MEPS comprising 23,612 individuals, which results

in a survey response rate of 78 percent. This figure

reflects participation in both NHIS and MEPS.

The statistics presented in this

report are affected by both sampling error and sources

of nonsampling error, which include nonresponse bias,

respondent reporting errors, and interviewer effects.

For a detailed description of the MEPS survey design,

the adopted sample design, and methods used to minimize

sources of nonsampling error, see J. Cohen (1997), S.

Cohen (1997), and Cohen, Monheit, Beauregard, et al.

(1996). The MEPS person-level estimation weights include

nonresponse adjustments and poststratification adjustments

to population estimates derived from the March 1996 Current

Population Survey (CPS) based on cross-classifications

by region, age, race/ethnicity, and gender.

Tests of statistical significance

were used to determine whether the differences between

populations exist at specified levels of confidence or

whether they occurred by chance. Differences were tested

using Z-scores having asymptotic normal properties at

the 0.05 level of significance. Unless otherwise noted,

only statistically significant differences between estimates

are discussed in the text.

1987 NMES

The NMES Household Survey was designed

to produce statistically unbiased national estimates

that are representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized

population of the United States. To this end, the Household

Survey used the national multistage area samples of Westat,

Inc., and the National Opinion Research Corporation (NORC).

An initial screening interview was

conducted in fall 1986 to facilitate oversampling of

population subgroups of particular policy concern (i.e.,

blacks, Hispanics, the elderly, the poor and near poor,

and those with difficulties in ADLs). Screening interviews

were completed in approximately 28,700 dwelling units.

Sampling specifications required the selection of approximately

17,500 households for the first core household interview.

Data were obtained for about 85.4 percent of eligible

households in the first interview. Approximately 6 percent

of all survey participants provided data for only some

of the time in which they were eligible to respond. In

the Household Survey, the full-year core questionnaire

response rate was 80.1 percent and the joint core questionnaire/health

questionnaire/access supplement response rate was 72.0

percent. For a detailed description of the survey design

and of sampling, estimation, and adjustment methods,

including weighting for nonresponse and poststratification,

see Cohen, DiGaetano, and Waksberg (1991).

Rounding

Estimates presented in the tables

were rounded to the nearest 0.1 percent. Standard errors,

presented in Tables A-F, were rounded to the nearest

0.01. Therefore, some of the estimates for population

totals of subgroups presented in the tables will not

add exactly to the overall estimated population total.

Standard Error

Tables

Table A. Standard errors for demographic

characteristics of percent of U.S. population with

Medicaid: U.S. community population, first half of

1996 and first half of 1987. Corresponds to Table 1.

Source: Center

for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

Household Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical

Expenditure Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table B. Standard errors for demographic

characteristics of the Medicaid population: U.S. community

population, first half of 1996 and first half of 1987.

Corresponds to Table 2.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical Expenditure

Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table C. Standard errors for employment

status of parents of Medicaid-enrolled children age

I8 and under: U.S. community population, first half

of 1996 and first half of 1987.

Corresponds to Table 3.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1); National Medical Expenditure

Survey Household Survey, 1987 (Round 1).

^top

Table D. Standard errors for health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled children age

18 and under: U.S. community population, first half

of 1996.

Corresponds to Table 4.

- aItem nonresponse was

less than 0.1 percent of all responses. Distributional

estimates on health status were made on the assumption

that nonrespondents followed the distribution of respondents.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

Table E. Standard errors for health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled adults ages 19-64:

U.S. community population, first half of 1996.

Corresponds to Table 5.

-

aItem

nonresponse was 0.6 percent of all responses. Distributional

estimates

on health status were made on the assumption that

nonrespondents followed the distribution of respondents.

-

bActivities

of daily living (ADLs) include activities such

as bathing

and dressing. Instrumental activities of daily

living (IADLs) include activities such as shopping

and paying

bills.

-

cLimitations involve

the ability to work at a job, do housework, or go

to school.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

Table F. Standard errors for health

status of total and Medicaid-enrolled adults age

65 and over: U.S. community population: first half

of 1996.

Corresponds to Table 6.

-

aItem

nonresponse was 1.5 percent of all responses. Distributional

estimates

on health status were made on the assumption that

nonrespondents followed the distribution of respondents.

-

bActivities

of daily living (ADLs) include activities such

as bathing

and dressing. Instrumental activities of daily

living (IADLs) include activities such as shopping

and paying

bills.

-

cLimitations involve

the ability to work at a job, do housework, or go

to school.

Source: Center for Financing,

Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household

Component, 1996 (Round 1).

^top

Notes

1The

institutionalized Medicaid population has been excluded

from this analysis.

2Aid

to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was replaced

by Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), which

went into effect in 1997. SSI stands for Supplemental

Security Income.

^top

Suggested Citation:

Banthin, J. S. and Cohen,

J. W. Research Findings #9: Changes in the Medicaid Community Population: 1987-96. August 1999. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/rf9/rf9.shtml |

|