Skip to main content

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

STATISTICAL BRIEF #548:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 2023 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rebecca Ahrnsbrak, MPS, Emily Mitchell, PhD, and Zhengyi Fang, MS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Highlights

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IntroductionThe onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 significantly disrupted the healthcare landscape in the United States. A survey conducted in June 2020 found that an estimated 40.9 percent of adults in the United States had delayed or avoided medical care, with about a third of adults having avoided routine care and 12.0 percent avoiding emergency care.1 Evidence also suggests that widespread adoption of mitigation measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 contributed to historically low influenza activity in 2020.2 A recent analysis of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) data from 29 states found a 25.7 percent decrease in the total number of emergency department visits in April through December of 2020 compared with the same timeframe in 2019, with particularly large declines in treat-and-release emergency department visits for infectious respiratory diseases such as influenza and acute bronchitis.3This Statistical Brief presents trends for the most commonly treated medical conditions from 2016 to 2020 among the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Healthcare treatment for a condition includes office-based medical visits, hospital outpatient visits, emergency room visits, hospital inpatient stays, prescribed medicine fills, and home healthcare. The analysis includes collapsed condition categories with at least 25 million treated people in any year from 2016 to 2020. Although the categories for symptoms and other care and screening also surpassed this threshold, we excluded them from this report because these reasons for receiving healthcare can be associated with a wide range of possible medical conditions or may not be associated with a specific medical condition at all. Estimates by condition are presented separately for those who received any office-based or hospital outpatient healthcare, those who had emergency room visits or hospital inpatient stays, and those who were treated with prescribed medicines. This Brief highlights changes in treated prevalence for these common conditions in 2020 relative to the years 2016 to 2019. Estimates are based on the 2016 to 2020 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) public use files. All differences between estimates discussed in the text are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless otherwise noted. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

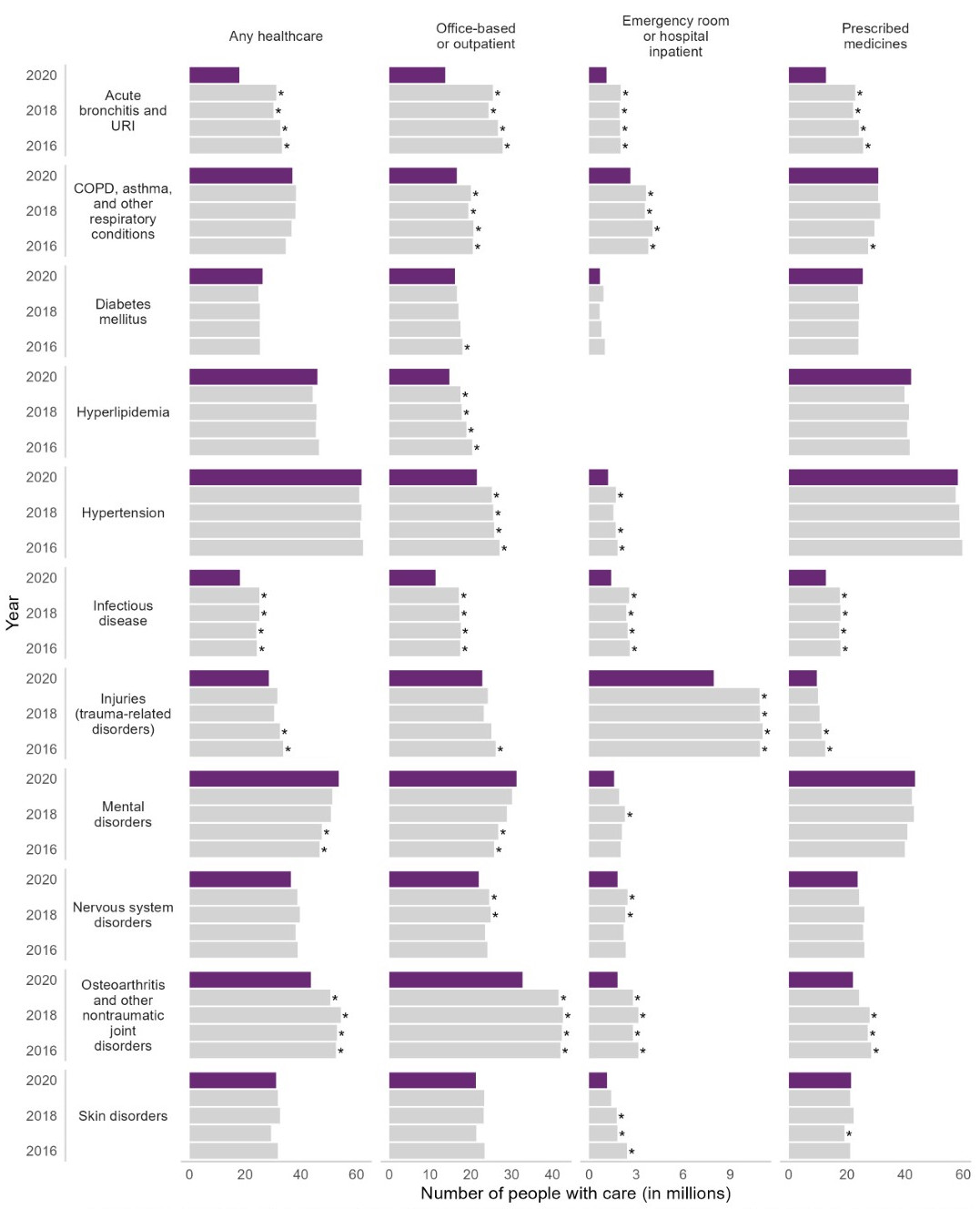

FindingsTotal treated population (figure 1)The estimated treated population for several conditions declined significantly in 2020 compared with the four previous years. Treated prevalence for acute bronchitis and upper respiratory infections (URIs) decreased from 31.2 million in 2019 to 17.9 million in 2020, a 42.8 percent decline. The estimated population treated for infectious disease (excluding COVID-19) declined 27.9 percent, from 25.1 million in 2018 and 2019 to 18.1 million in 2020. An estimated 43.6 million people were treated for osteoarthritis and other nontraumatic joint disorders in 2020, a 13.8 percent decline from the 50.5 million in 2019. The estimated treated prevalence for each of these conditions in 2020 was lower than each year from 2016 to 2019.While the estimated 2020 population treated for mental disorders (53.6 million) was higher than both 2016 and 2017, it was not statistically different from 2018 or 2019. Population with office-based or outpatient medical visits (figure 1)Many commonly treated health conditions saw significant decreases in the estimated population receiving care in office-based or outpatient hospital settings in 2020. The estimated number of people receiving care in an office-based or outpatient setting was lower in 2020 than for all years from 2016 to 2019 for acute bronchitis and URIs; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and other respiratory conditions; hyperlipidemia; hypertension; infectious disease; and osteoarthritis and other nontraumatic joint disorders. The largest percentage decline in people treated in office-based or outpatient settings between 2019 and 2020 occurred for acute bronchitis and URIs, which fell 46.1 percent (from 25.4 million to 13.7 million). From 2019 to 2020, the number of people receiving office-based or outpatient care decreased 33.7 percent for infectious disease (17.1 million to 11.3 million); 21.3 percent for osteoarthritis and other nontraumatic joint disorders (41.5 million to 32.6 million); 17.3 percent for COPD, asthma, and other respiratory conditions (20.0 million to 16.5 million); 15.4 percent for hyperlipidemia (17.4 million to 14.7 million); and 14.6 percent for hypertension (25.1 million to 21.4 million).The estimated number of people receiving care for mental disorders in an office-based or outpatient setting in 2020 was 31.1 million, which was higher than in 2016 and 2017 but not statistically different from 2018 or 2019. Population with emergency room visits or hospital inpatient stays (figure 1)Similarly to office-based and outpatient visits, the estimated number of people treated in an emergency room or hospital inpatient stay decreased in 2020 for most of the commonly reported health conditions. The largest percentage decline in people treated in an emergency room or hospital inpatient stay between 2019 and 2020 occurred for acute bronchitis and URIs, which decreased 45.0 percent (from 2.0 million to 1.1 million), followed closely by infectious disease at 44.9 percent (2.6 million to 1.4 million). Other conditions with a significant decline in emergency room or hospital inpatient care from 2019 to 2020 include COPD, asthma, and other respiratory conditions (3.6 million to 2.6 million); hypertension (1.7 million to 1.2 million); injuries (10.9 million to 7.9 million); nervous system disorders (2.5 million to 1.8 million); and osteoarthritis and other nontraumatic joint disorders (2.8 million to 1.8 million). The estimated population treated for skin disorders in an emergency room or hospital inpatient stay in 2020 (1.1 million) was lower than each year from 2016 to 2018 but not statistically different from 2019.Population with prescribed medicine fills (figure 1)The number of people obtaining prescribed medicines for these conditions generally experienced fewer changes in 2020 than for other types of healthcare. The largest percentage declines in people treated with prescribed medicines between 2019 and 2020 were for acute bronchitis and URIs, which declined by 44.0 percent (from 22.8 million to 12.8 million), and infectious disease, which declined by 27.2 percent (17.5 million to 12.8 million). The 2020 estimates for these conditions were lower than for all years from 2016 to 2019.The estimated number of people with prescribed medicine fills for injuries or osteoarthritis and other nontraumatic joint disorders declined in 2020 compared with 2016 to 2019, but this difference was not statistically significant for all years. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Data SourceThe estimates reported in this Brief are based on data from the following Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data files:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DefinitionsHealth conditionsThe health conditions reported in this Statistical Brief were the most commonly treated conditions reported from 2016 to 2020 and are not mutually exclusive. People were classified as treated for a particular condition if they had one or more healthcare events (i.e., office-based, hospital outpatient or emergency room visits, hospital inpatient stays, prescribed medicine fills, or home healthcare) where the condition was reported as leading to or having been discovered during the event. Conditions reported by the household were coded into International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, which were then collapsed to Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) codes (see https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp for details). Similar CCSR codes were further grouped into broader condition categories. The conditions discussed in this brief were defined as follows:

Type of service

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About MEPS-HCThe Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) collects nationally representative data on healthcare use, expenditures, sources of payment, and insurance coverage for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. The MEPS-HC is cosponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). More information about the MEPS-HC can be found on the MEPS website at https://meps.ahrq.gov/. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ReferencesFor a detailed description of the MEPS-HC survey design, sample design, and methods used to minimize sources of nonsampling error, see the following publications:Cohen, J. Design and Methods of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component. MEPS Methodology Report #1. AHCPR Pub. No. 97-0026. July 1997. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), Rockville, MD. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/mr1/mr1.pdf Ezzati-Rice, T. M., Rohde, F., and Greenblatt, J. Sample Design of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, 1998-2007. Methodology Report #22. March 2008. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/mr22/mr22.pdf Machlin, S. R., Chowdhury, S. R., Ezzati-Rice, T., DiGaetano, R., Goksel, H., Wun, L.-M., Yu, W., and Kashihara, D. Estimation Procedures for the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component. Methodology Report # 24. September 2010. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/mr24/mr24.shtml Stagnitti, M. N., Beauregard, K., and Solis, A. Design, Methods, and Field Results of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Medical Provider Component (MEPS MPC)—2006 Calendar Year Data. Methodology Report #23. November 2008. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/mr23/mr23.pdf Zuvekas SH, Kashihara D. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(12):2157-2166. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306534. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Suggested CitationAhrnsbrak, R. D., Mitchell, E. M., and Fang, Z. Treated Prevalence of Commonly Reported Health Conditions, 2016 to 2020. Statistical Brief #548. May 2023. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st548/stat548.shtmlAHRQ welcomes questions and comments from readers of this publication who are interested in obtaining more information about access, cost, use, financing, and quality of healthcare in the United States. We also invite you to tell us how you are using this Statistical Brief and other MEPS data and tools and to share suggestions on how MEPS products might be enhanced to further meet your needs. Please email us at MEPSProjectDirector@ahrq.hhs.gov or send a letter to the address below: Joel W. Cohen, PhD, Director Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 5600 Fishers Lane, Mailstop 07W41A Rockville, MD 20857 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1. Treated prevalence by condition, healthcare type, and year

* Statistically significant vs. 2020 at alpha=0.05 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1a. Comparison of the total treated population (in millions) between 2020 and 2016-2019

Note: *Statistically significant at alpha=0.05. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1b. Comparison of the population (in millions) with office-based or outpatient medical visits between 2020 and 2016-2019

Note: *Statistically significant at alpha=0.05. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1c. Comparison of the population (in millions) with emergency room visits or hospital inpatient stays between 2020 and 2016-2019

Note: *Statistically significant at alpha=0.05. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1d. Comparison of the population (in millions) with prescribed medicine fills between 2020 and 2016-2019

Note: *Statistically significant at alpha=0.05. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1 Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of

COVID-19-related concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257.

Published 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||